Women are openly accepted and encouraged to experience the fullest participation in all chivalric and knightly activities, quests and missions of the Order of the Temple of Solomon. In the restored Templar Order, women also have equal opportunity to serve in high-level governmental positions as Crown Officers. This is a powerful way to exemplify female leadership in the spirit of Saint Joan of Arc, in the historic tradition of Saint Mary Magdalene.

Women are openly accepted and encouraged to experience the fullest participation in all chivalric and knightly activities, quests and missions of the Order of the Temple of Solomon. In the restored Templar Order, women also have equal opportunity to serve in high-level governmental positions as Crown Officers. This is a powerful way to exemplify female leadership in the spirit of Saint Joan of Arc, in the historic tradition of Saint Mary Magdalene.

Although Chivalry of the Middle Ages and Renaissance generally excluded women from most chivalric Orders, the historical record proves that women were actually very much included within the Order of the Temple of Solomon. Medieval Templar rules which appear to restrict the participation of women were merely to provide a reasonable degree of separation, to ensure modesty and respect.

Although Chivalry of the Middle Ages and Renaissance generally excluded women from most chivalric Orders, the historical record proves that women were actually very much included within the Order of the Temple of Solomon. Medieval Templar rules which appear to restrict the participation of women were merely to provide a reasonable degree of separation, to ensure modesty and respect.

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD evidences an original pre-existing “practice” (during the first 10 years of the Order), that women were in fact “received as Sisters in the Order”, not as a “custom” but as a traditional exception, providing only a reasonable degree of separation for modesty (Rule 70).

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD evidences an original pre-existing “practice” (during the first 10 years of the Order), that women were in fact “received as Sisters in the Order”, not as a “custom” but as a traditional exception, providing only a reasonable degree of separation for modesty (Rule 70).

Proving that women were in fact admitted to the Order, it requires all Templars to “refuse to be godfathers or godmothers”, specifically using the additional word referring to women in active Templar service (Rule 72). The fact of women as “Sisters” in full and equal membership is confirmed by the later rule which commands to “pray… for our Brothers and for our Sisters” (Rule 541, ca. 1150 AD).

The active support of women in the Order is further confirmed by the later rule allowing a Knight to receive “services of a woman” for assistance, “by permission” for any appropriate purpose (Rule 679, ca. 1290 AD). [1]

Manuscripts preserved by the Teutonic Order also evidence that in 1305 AD, the Templar Order acquired at least one female monastery, the “Abbey des Camaldules de Saint Michel de Lemo”, and the “Abess Agnès” professed Templar Vows and was admitted by the Templar Prior from Venice. [2]

Based upon these facts from the historical record, the Order traditionally recognizes women as equal to, but venerably different from, their male counterparts, all serving in balance and harmony as Templar Brothers and Sisters.

By the protocols of medieval Chivalry and related rules on titles, chivalric Orders never used the same word for men and women of equal status, and never used masculine militarized words as titles for women of the same position. This custom is deeply rooted in French language (as French culture greatly influenced chivalric traditions), in which certain words are exclusively “masculine” or “feminine” as a matter of basic grammar.

By the protocols of medieval Chivalry and related rules on titles, chivalric Orders never used the same word for men and women of equal status, and never used masculine militarized words as titles for women of the same position. This custom is deeply rooted in French language (as French culture greatly influenced chivalric traditions), in which certain words are exclusively “masculine” or “feminine” as a matter of basic grammar.

Women were treated as equal, but venerably different, emphasizing unique feminine qualities which were deemed essential pillars of historical institutions and of civilization itself. Accordingly, women of equal leadership, influence and participation were given alternative and equivalent titles worthy of their revered feminine qualities.

Under the Temple Rule of 1129 AD, the primary general membership in the Order actually held the title of “Sergeant” (Rules 67-68), a word only appropriate for men. For women, the alternative title equivalent to Sergeant, from the same French military system, is “Adjutante” (pronounced like “debutante”). The female title of Adjutante comes from the Latin ‘adjutare‘ meaning to “support”, based on the root ‘iuvare‘ meaning “to give strength” [3]. The title of Adjutante thus expresses a special respect for women as necessary support within the chivalric Order, as the essential source of strength for their male counterparts.

For women in full chivalric status, at the same level as Knights, the historically correct title is that of “Dame”. Experts in chivalric protocols confirm that:

“A Dame is the female equivalent of a Knight of an order of chivalry.” The title “Dame” is always used in the same way as “Sir” for a Knight. [4]

The word “Dame” (properly pronounced “daame”) is the original word in early 13th century Old French, from the Late Latin ‘domna‘, from Old Latin ‘domina‘, which means “lady ruler of the house”, in the same sense as men were called “master”. Only in modern American English, “Dame” became a short-lived slang word, first used in 1902, briefly popularized by Hollywood movies in the 1940’s, simply meaning a “strong woman”.

“Dame” is defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “a woman of rank, station or authority” and “a female member of an order of knighthood”, listing the synonyms “matriarch” and “matron”. [5] [6]

The title of “Dame”, which a woman holds in her own right, earned by her own merit, should never be confused with “Lady”, which is only used by the wife of a Knight. The prefix “Lady” is merely a “courtesy title” held only by marriage, and can be lost upon divorce, or lost if a widow remarries. [7]

Although some women may think they prefer the sound of “Lady”, as popularized by Arthurian or Renaissance themes in literature and entertainment, it is not an alternative. Any woman of equal chivalric status to a Knight must be respected by using the proper historical title of “Dame”.

In correct chivalric terminology, as a Knight is “knighted” by being “dubbed” and receives “knighthood”, a Dame is “appointed” by being “presented” with the honour and receives “damehood”. [8]

Both men and women, as Sergeants and Adjutantes, Knights and Dames, are all “Templars”, equal as Templar Brothers and Sisters, and all are in chivalric service in the Order. Indeed, it is the status of being a “Templar” that is prized and revered, not merely the respective gender denominations.

There are many historical precedents for armed women in chivalric service, including women actively participating in predominantly male Orders of Chivalry.

There are many historical precedents for armed women in chivalric service, including women actively participating in predominantly male Orders of Chivalry.

During ancient times in both Britain and France, women of the Celtic civilization were regularly known to be great warriors, and sometimes notable military commanders or leaders of whole armies. The most famous of ancient female military leaders was the Celtic “Warrior Queen” named “Boudicca“, who commanded an army based upon her skills and authority as a Druid High Priestess. [9]

Joan of Arc was the quintessential embodiment of that ancient practice from Queen Boudicca, which was manifested in the famous “warrior monk” character of the Knights Templar, who preserved the most ancient Priesthood of Solomon. Always prayerful and persistently in direct divine communion, Joan of Arc was truly qualified as a High Priestess, according to ancient traditions which were understood, preserved and continued by the Templar Order. Through constant prayer and meditation, she experienced visions from God and visitations by Saints and Angels, receiving surprisingly accurate prophecies of near-future events that consistently proved to be true.

During the 12th century, the Teutonic Order (a branch of the Templar Order) accepted women as “Sisters” (‘Consorores’) who wore its chivalric habit and lived by its Rule. These Sisters were in active service of hospitaller functions, but not military activities, and multiple convents were formed under otherwise “male” military Orders.

In the 12th century Order of Saint John (Malta), women were given the title “Sisters of Hospitality” (‘Soeurs Hospitalières’). There were chivalric Hospitaller convents in Aragon, France, Spain and Portugal, until at least ca. 1300 AD, and in Buckland England until 1540 AD. The Prioress of a convent was given the title of ‘Commendatrix’. [10]

Also in the 12th century, the Order of the Hatchet was created by the Count of Barcelona in 1149 AD, for the women of Tortosa in Aragon, who defended and freed the city when the battle-worn men could not find reinforcement soldiers. The women were all made hereditary Dames of the chivalric Order, and thereafter were treated as female military “Knights”. They were given the titles of ‘Equitissae’ (from ‘Equites’) and ‘Militissae’ (from ‘Milites’) [11] [12]

The earliest use of the title ‘Militissa’ as a “female Knight” was the Order of the Glorious Saint Mary founded in Bologna, Italy in 1233 AD, and approved by the Vatican in 1261 AD, until it was suppressed by a later Pope in 1558 AD. In France, other chivalric Orders of women were founded in 1441 AD and 1451 AD, granting the French title ‘Chevalière’ (feminine form of Chevalier) or the Latin title ‘Equitissa’. Continuing into the 17th century, the female Canons of the Monastery of Saint Gertrude in Nivelles were “knighted” with the titles ‘Militissae’, and were given the accolade of dubbing with a sword at the altar. [13] [14] [15]

In Old French since the 14th century, women held the title ‘Chevaleresse’ in connection with acquiring a male fiefdom conceded by a man, or as the wife of a Knight, and the title ‘Chevalière’ as a Dame of an Order. [16]

Chivalric culture of the Middle Ages developed a theme known as “Les Neuf Preuses” (“The Nine Worthy-Women”). The Preuses were presented as a row of statues or engraved portraits, depicting variously selected sets of nine inspirational women, from differing lists according to local popular culture. The Preuses were women who changed history, many of them through chivalric warfare in battle.

The Castle of Pierrefonds near Paris features a beautiful row of nine Preuses (ca. 1850 AD), three of them holding a sword, lance and battle hammer, respectively. [17]

Among the most revered women on various lists of Nine Preuses during the 15th century were Queen Boudicca, the warrior High Priestess who led the Celts in battle against the Romans (ca. 60 AD), and many venerated female Saints including Joan of Arc.

Several precedents for women in Grand Cross leadership (analogous to the Templar Grand Mastery) in chivalric Orders of the Renaissance are found in the Order of Saint John (Malta):

Anne-Claude-Louise d’Arpajon (1729-1794 AD) held a hereditary Damehood created as passing through female lines, and became a Grand Cross in 1745 AD. The Mémoires de Hénault de Noailles (ca. 1750 AD) documented three other women who became Grand Cross during the mid-18th century: The Italian Princesse de Rochette, the Princess of Thurn und Taxis (Maria Ludkova von Lobkowicz), and her daughter the Duchess of Wurtemberg (Maria Augusta von Thurn und Taxis). [18]

In Chivalric Orders under the Vatican, traditionally they have an “Order of Cloistered Nuns”, and “also associations whose associate members are both male and female”, as in the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM). [19]

Later in the 19th century, for the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, in 1888 AD the Vatican “extended the knighthood to the female[s] with the title of Dame, while all [other] Orders of the Holy See were reserved only for the male[s].” [20] [21]

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431 AD) was in fact a hereditary Templar, as the genealogical Countess of Anjou, the dynastic house of the Templar King Fulk d’Anjou of Jerusalem (1089-1143 AD), as the founding Royal Patronage of the Templar Order. Joan of Arc descended through two Counts of Anjou, Karl I of Frankreich (1270-1325 AD) and Karl II of Lahme (1248-1309 AD) who was also King of Jerusalem. [22] The cherished sword of Joan of Arc was named after Saint Catherine de Fierbois (of Alexandria), a patron Saint of the Knights Templar, and its blade was engraved with the heraldic Cross of Jerusalem. [23]

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431 AD) was in fact a hereditary Templar, as the genealogical Countess of Anjou, the dynastic house of the Templar King Fulk d’Anjou of Jerusalem (1089-1143 AD), as the founding Royal Patronage of the Templar Order. Joan of Arc descended through two Counts of Anjou, Karl I of Frankreich (1270-1325 AD) and Karl II of Lahme (1248-1309 AD) who was also King of Jerusalem. [22] The cherished sword of Joan of Arc was named after Saint Catherine de Fierbois (of Alexandria), a patron Saint of the Knights Templar, and its blade was engraved with the heraldic Cross of Jerusalem. [23]

The historical precedent of Saint Joan of Arc demonstrates that feminine expressions of chivalric nobility, such as the proper title of “Dame”, are not “less than” those of their male counterparts. Saint Joan’s example highlights that women are equally important in their own right, and are honoured for their own unique qualities, embodying the principle of the “feminine face of God”, or the “divine feminine” aspect of God. Perhaps most importantly, Joan of Arc illustrates that women should not suppress their sacred feminine nature, and should not seek respect by transforming themselves into “men”.

The divine feminine principle cannot be respected by suppressing it, only to be replaced with the counterbalancing male aspect. To honour the divine feminine necessarily requires recognition and celebration that it is in fact “feminine”, and prohibits that it be disguised and forced to be accepted only through conformity with the masculine principle.

Indeed, the most ancient sacred wisdom of spiritual alchemy – the true concept of the legendary “Holy Grail” – was never to transform all feminine energies into masculine, but rather to combine distinctly unique male and female polarities of esoteric energy in equal balance, as the best possible channel for the power of the Holy Spirit.

Joan of Arc obtained command over an army not by denying her femininity, but by concentrating on the unique differences and contributions of her true feminine power. There were already many male Generals capable of relentless aggression and cunning strategy, but none who had the advantage of feminine intuition rooted in divine communion, an alternate female perspective necessary to shed new light on old military strategies, and a characteristically female emotional quality that could so profoundly inspire the hearts of all the soldiers to the most extraordinary bravery.

Saint Joan of Arc did not transform herself into a “man”, but nobly led an army as a true woman. The historical record proves that she dressed in men’s clothes and wore short hair only as practical battle wear, as a defensive measure to deter and prevent molestation, and to hide her identity in enemy territory – but never to suppress nor deny her femininity.

Conversely, she did not vanquish enemies by asserting supposed “independence” to dismiss and replace men as “not needed”, but rather applied her uniquely feminine qualities to most effectively lead an army of men, fighting together in equal balance. She thereby consciously combined the male-female difference into a powerful blend of perfection, directly embodying the ancient secrets of Templar spiritual alchemy, as the core esoteric principle of the Holy Grail itself.

Joan of Arc was a true Templar, and was revered and honoured as a Templar Dame, becoming a famous legend in her own right, of equal to or even greater renown than any Arthurian or Templar Knights.

Indeed, she was even canonized as a Saint, an honour that was never given to the historical figure who was later popularized as the literary “King Arthur” (the 6th century Prince Arthur Aidan), nor to any of the Templar Grand Masters, not even the Martyr Jacques de Molay. Thus, Saint Joan represents the pure manifestation of the unlimited power of authentically being a Templar Dame.

In reverent dedication to this more enlightened understanding of the feminine principle in Chivalry, the Order of the Temple of Solomon recognizes all Dames as fully equal to, but venerably different from, their male counterpart Knights, all serving in balance and harmony as Templars. Men and women serve together as equal Brothers and Sisters in the Templar family, distinguished only by the proper respective grammatical forms of their official chivalric and nobility titles in the Order.

In traditional British Royal Chivalry, for investiture of a Dame, a woman is not supposed to kneel (as this is inconvenient with a Medieval, Renaissance or Victorian era dress of a noblewoman), and is not supposed to be dubbed with a sword (considered inconsistent with their feminine qualities, and potentially painful). Instead, a woman is “presented” with her damehood, by “placing the correct decoration on a cushion” for the Dame to receive her badge of regalia. [24]

In traditional British Royal Chivalry, for investiture of a Dame, a woman is not supposed to kneel (as this is inconvenient with a Medieval, Renaissance or Victorian era dress of a noblewoman), and is not supposed to be dubbed with a sword (considered inconsistent with their feminine qualities, and potentially painful). Instead, a woman is “presented” with her damehood, by “placing the correct decoration on a cushion” for the Dame to receive her badge of regalia. [24]

In the modern Order of the Temple of Solomon, women are provided the iconic experience of the “accolade”, although kneeling is optional. Faithful to the sacred symbology of Templar heritage, women can be “dubbed” with a long-stemmed rose, honouring the ancient wisdom “under the rose”, and representing the divine feminine principle in the tradition of Saint Mary Magdalene.

However, there is a historical precedent that from the 12th century into the 17th century, the female Canons of the Monastery of Saint Gertrude in Nivelles France were “knighted” with the titles ‘Militissae’ (from male ‘Milites’), and were given the accolade of dubbing with a sword at the altar [25] [26]. True to this rare tradition, and also the major precedent of Saint Joan of Arc, women who desire and so request may be dubbed by the sword, as the historical record proves that such request should not be refused.

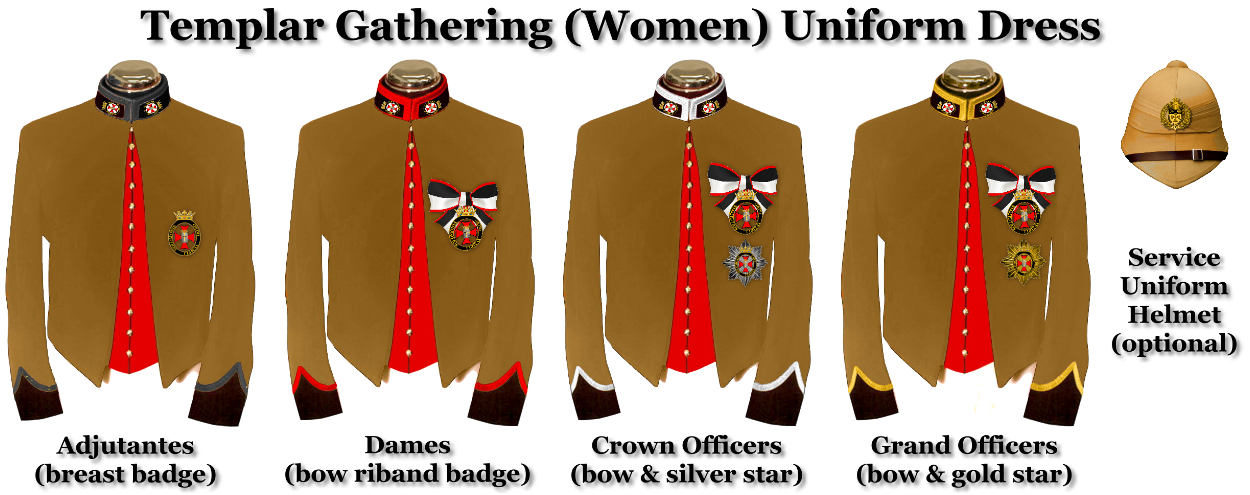

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD required “everyone to have the same” uniform (Rule 18) [27]. There is also historical precedent that in the 12th century Teutonic Order (a branch of the Templar Order), women as Sisters wore the same chivalric “habit” of regalia as the Brothers [28]. Accordingly, women in the Templar Order (Adjutantes and Dames) wear the same uniform as men (Sergeants and Knights).

Templar Gathering Uniforms (Women)

As part of adopting the 14th century Rules of Chivalric Regalia as codified in 1672 AD, the modern Order of the Temple of Solomon has reestablished proper use of the medieval Livery Badge and Livery Collar, as official insignia reserved for Chivalry and Nobility [29] [30], which were authorized to wear “at all feasts and in all companies” with all dress codes [31].

As a result, in situations where the uniform is not used, Templar Adjutantes and Dames can rightfully use the relevant chivalric badges and collars with smart casual dress, business dress and evening wear, fashionably expressing their authentic female Templarism in diverse situations.

Dame Regalia (Lounge & Formal)

Regalia Purchased Separately – Regalia must be purchased separately, after being installed as a Templar Adjutante in full membership. Regalia costs are not included in the subscriptions or donations made by members of the Order.

Illustrations May Enlarge Sizes – For the purposes of Illustration, regalia accessories and insignia may appear larger than their actual size proportional to the clothing, for better visibility of detail. Actual sizes are strictly and precisely in accordance with the international standard rules as used by all governments and legitimate chivalric Orders.

Learn about Saint Mary Magdalene in Knights Templar tradition.

Learn about Saint Joan of Arc as a dynastic Templar female warrior.

Learn details about General Membership in the Templar Order.

[1] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 70, 72, 541, 679.

[2] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, (1886), p.69, Note 1 to Rule 70; De Wal, Recherches sur l’Ordre Teutonique (1807), Vol.1, p.262.

[3] Douglas Harper, Online Etymology Dictionary (2015), “Adjutant”, “Aid”.

[4] Patrick Montague-Smith, Debrett’s Correct Form, 1st Edition, Kelly’s Directories, London (1970); Debrett’s Handbook, Debrett’s Peerage Ltd., London (2014); Debretts.com (online), “Forms of Address: Titles: Dame”.

[5] Douglas Harper, Online Etymology Dictionary (2015), “Dame”.

[6] Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Inc. of Encyclopedia Britannica (2015), “Dame”,

[7] Patrick Montague-Smith, Debrett’s Correct Form, 1st Edition, Kelly’s Directories, London (1970); Debrett’s Handbook, Debrett’s Peerage Ltd., London (2014); Debretts.com (online), “Forms of Address: Titles: Dame”, “Knight: Wife of a Knight”.

[8] Patrick Montague-Smith, Debrett’s Correct Form, 1st Edition, Kelly’s Directories, London (1970); Debrett’s Handbook, Debrett’s Peerage Ltd., London (2014); Debretts.com (online), “Forms of Address: Titles: Dame”, “People: Essential Guide to the Peerage: The Knightage”.

[9] David Manson, The Celts: Lost Treasures of the Ancient World, documentary film, produced by Cromwell Productions for the Discovery Channel (2000), at 38:12 min.

[10] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Women in the Military Orders”.

[11] Ashmole, The Institution, Laws and Ceremony of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (1692), Chapter 3, Section 3.

[12] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Female Orders of Knighthood”.

[13] Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See: A Historical, Juridical and Practical Compendium (1983).

[14] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Female Orders of Knighthood”.

[15] Charles du Fresne Du Cange, Glossarium Ad Scriptores Mediae Et Infimae Latinitatis, 17th century, Italian Edition, republished by Ulan Press (2012), “Militissa”.

[16] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Women Knights”.

[17] François Velde, The Nine Worthies, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “The Nine Worthies: Female Version”.

[18] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Female Grand-Cross in the Order of Saint John”.

[19] Saint Michael Academy of Eschatology, Regular Orders of the Holy See, West Palm Beach, Florida (2008), updated (2015), Free Course No.555: “Chivalric Orders”, Lesson 3, Part 4.

[20] Pope Leo XIII, Apostolic Letter (3rd August 1888).

[21] Saint Michael Academy of Eschatology, Regular Orders of the Holy See, West Palm Beach, Florida (2008), updated (2015), Free Course No.555: “Chivalric Orders”, Lesson 3, Part 4, “The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem”.

[22] Heinz Friederichs, Genealogisches Jahrbuch, academic journal of genealogy, Germany (ca.1971), pp.73-81.

[23] Fourth Private Examination of Joan of Arc, 27 February 1431, National Archives of France; See: Barrett, The Trial of Jeanne d’Arc (1931).

[24] Patrick Montague-Smith, Debrett’s Correct Form, 1st Edition, Kelly’s Directories, London (1970); Debrett’s Handbook, Debrett’s Peerage Ltd., London (2014); Debretts.com (online), “People: Essential Guide to the Peerage: The Knightage”.

[25] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “Female Orders of Knighthood”.

[26] Charles du Fresne Du Cange, Glossarium Ad Scriptores Mediae Et Infimae Latinitatis, 17th century, Italian Edition, republished by Ulan Press (2012), “Militissa”.

[27] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 18.

[28] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003),”Women in the Military Orders”.

[29] Peter Brown, A Companion to Chaucer, Wiley-Blackwell (2002), p.17.

[30] Chris Given-Wilson, Richard II and the Higher Nobility, in Anthony Goodman & James Gillespie, Richard II: The Art of Kingship, Oxford University Press (2003), p.126.

[31] Susan Crane, The Performance of Self, University of Pennsylvania Press (2002), p.19.

You cannot copy content of this page