How the Templar Order survived physically, as a living tradition through a canonical lineage of initiatory succession, thriving as an “underground” network, continuing into the modern era.

Notwithstanding the official narrative of mainstream “history” textbooks, the Order of the Temple of Solomon, as the sovereign institution of the Knights Templar, was never “dissolved” nor “disbanded” nor “suspended”, nor otherwise “extinguished” after the French Persecution of 1307 AD. Volumes of overlooked facts of “lost” history evidence that the Order was merely forced to operate as an “underground” network, preserving its sacred knowledge and continuing its missions, surviving until it could be safely restored in the future.

Notwithstanding the official narrative of mainstream “history” textbooks, the Order of the Temple of Solomon, as the sovereign institution of the Knights Templar, was never “dissolved” nor “disbanded” nor “suspended”, nor otherwise “extinguished” after the French Persecution of 1307 AD. Volumes of overlooked facts of “lost” history evidence that the Order was merely forced to operate as an “underground” network, preserving its sacred knowledge and continuing its missions, surviving until it could be safely restored in the future.

A close examination of facts in the historical record proves that the Templar Order survived physically, as a living tradition of Templars through a legitimate canonical lineage of initiatory succession. The Order thus continued to advance European culture and civilization, leading humanity into the Renaissance.

A close examination of facts in the historical record proves that the Templar Order survived physically, as a living tradition of Templars through a legitimate canonical lineage of initiatory succession. The Order thus continued to advance European culture and civilization, leading humanity into the Renaissance.

Through the strategies established by founding Templars, surviving generations of the Templar Order continued to dramatically influence the development of Western Europe, as evidenced by signature Templar advancements in Switzerland and Scotland. The Knights Templar successfully survived, and indeed thrived, as an underground network, for centuries and into the present day.

Here, in this work from the original and restored Order of the Temple of Solomon, the world can finally discover the true history of the real survival and continuation of the Templar Order into the modern era.

The details of Templar survival presented here focus on the facts most relevant to supporting the later modern Restoration of the Templar Order.

Saint Bernard de Clairvaux was mentored by the Cistercian Saint Stephen Harding of Citeaux, who commissioned the original founding mission of the first Knights Templar for the Cistercian Order, to recover the Ancient Priesthood from the Temple of Solomon as the earliest origins and foundations of Christianity [1].

The Cistercian Saint Bernard then developed the Temple Rule of 1129 AD, actually based upon the earlier foundations of the Templar Order from 1118 AD, with the first Grand Master Hughes de Payens from 1120 AD [2].

Saint Bernard thus became a founding Patron of the original Templar Order, promoting and strategically arranging its support from the Vatican.

‘San Bernardo Abad: Doctor Mariano’ by Miguel Cabera (ca. 1750 AD) in Acervo del Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico (Detail)

Only six years after the Vatican granted additional Sovereign Protection to the Templar Order by Omne Datum Optimum of 1139 AD, Saint Bernard, as part of his Templar missions as Patron of the Order, established a “backup plan” in 1145 AD, as the original “insurance policy”, to ensure the survival and enable the restoration of the Order in the future.

This plan arranged for canonical preservation of the Templar Order, through the Ancient Priesthood recovered from the Temple of Solomon, continued as the Templar Priesthood.

In 1145 AD, the Cistercian Saint Bernard de Clairvaux caused Pope Eugene III to grant autonomy to Bishops in Utrecht, Netherlands as a “Cathedral Chapter”, which marked the formal beginning of the “Independent Church Movement”.

Eugene III was the first Cistercian to become Pope, who was mentored by Saint Bernard at the Monastery of Clairvaux, and was thus a loyalist of Saint Bernard supporting the Templar Order. [3] [4]

This Independent Church Movement was established in Utrecht under the Teutonic Knights, as an official branch of the Templar Order:

Throughout the development of this Movement (1145-1520 AD), Utrecht was a sovereign Principality of the Teutonic Order under its Prince Grand Masters (for approximately 114 years from ca. 1466-1580 AD) [5]. The Teutonic Order was essentially an autonomous branch of the Knights Templar, founded in the Templar stronghold of Acre in 1190 AD (under the Templar Principality of Antioch for 61 years from 1129 AD) [6].

As a result, this strategy placed the Independent Church Movement within the realm of control of the Templar Order, while giving it autonomy to be used to recover and restore the Order from external independent institutions, in the event that the Order might become unable to restore itself.

In 1215 AD, the Vatican’s Fourth Lateran Council confirmed the Independent Church Movement from Pope Eugene III as “independent” Churches (Canon 3), recognizing “ancient privileges” of “their [own] jurisdiction” (Canon 5), with autonomy as “cathedral churches” (Canons 10-11), providing that they can independently consecrate their own Bishops (Canon 23) [7].

These facts prove that the Independent Church Movement was established by Saint Bernard as part of the original 12th century founding strategies for the preservation, survival and later restoration of the Templar Order.

Legal Strategy of “Templar Lines” – Saint Bernard knew that succession for survival of an Order of Chivalry is not hereditary, as Grand Masters were always elected and never hereditary [8] [9].

He understood that it was necessary to establish a special type of “Templar Lines”, which would legally carry full institutional succession of all rights and authorities of the Templar Order, under specific doctrines of customary international law [10], royal and nobiliary law [11], and Canon law [12].

By that lineage of Sovereign Succession, the Templar Order could be legally Reestablished to full legitimacy by a Royal or Pontifical institution with a proven historical connection to the Knights Templar, under customary international law [13] [14] [15], and Canon law [16].

For this purpose, the strategy implemented by Saint Bernard was to use Vatican lineages of Apostolic Succession, to carry canonical lineages of Sovereign Succession for the Templar Order, all “hidden in plain sight”. Later, when needed for a future Reestablishment and restoration of the Templar Order, those Apostolic lines could be openly named “Templar Lines”.

(See details of Legal Succession of the Templar Order)

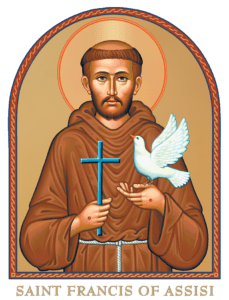

Following the strategic plan of Saint Bernard, Saint Francis of Assisi (1181-1226 AD) provided strong support to preserve and continue the “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession, carrying the lineage of Sovereign Succession of the Templar Order, within the Independent Church Movement from 1145 AD. The Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi was established in England in 1212 AD, led by Bishops from the Vatican, maintaining cooperation with the Vatican, while remaining autonomous through the Independent Church Movement.

Following the strategic plan of Saint Bernard, Saint Francis of Assisi (1181-1226 AD) provided strong support to preserve and continue the “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession, carrying the lineage of Sovereign Succession of the Templar Order, within the Independent Church Movement from 1145 AD. The Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi was established in England in 1212 AD, led by Bishops from the Vatican, maintaining cooperation with the Vatican, while remaining autonomous through the Independent Church Movement.

Autonomous Franciscan Order – The mainstream Franciscan “Order of Friars Minor” was founded by Saint Francis with the Franciscan Rule of 1209 AD, ratified by the Vatican.

Three years later, the lesser known “Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi” was established as the original Franciscan Mission to England in 1212 AD, and became an autonomous “Secular Franciscan Order” for non-monastic Clergy and missionaries, as established by Saint Francis in 1221 AD. (Originally called “Sacred Order of Franciscan Missionaries”, it was renamed when Francis was canonized as a Saint in 1228 AD.) [17]

The Vatican Order did not establish monasteries in England until twelve years later in 1224 AD. Vatican records establish that: “From 1239… The chapter of [monastic] custodies… ceased to exist” [18]. “[In] 1887 the [other] English houses [i.e. missions] were declared an independent custody” [19].

As a Mission which was never a monastery, and thus remained independent from the Vatican, the Sacred Order was part of the Independent Church Movement of Saint Bernard (from 67 years earlier), since its inception in 1212 AD. The Sacred Order soon took a leading role in the Movement, establishing its “Synod of Independent Apostolic Clergy” in 1221 AD.

The Sacred Order of Saint Francis was officially recognized by the Church of England as the Franciscan Anglican Mission since 1212 AD, later granted Full Communion with the Anglican Church since 1931 AD. [20]

Franciscan Templar Cooperation – When the Franciscan Sacred Order was founded in England in 1212 AD, the Knights Templar dominated England, having the strongest influence in advancing European civilization:

The Templar Order had its first Commandery at Garway Church of Hereford since 1180 AD, and its Headquarters of Temple Church in London since 1185 AD. The Order established the independent Legal Profession at Chancery Lane, and created the Inns of Court system for Common Law, by ca. 1189 AD [21] [22]. The Knights Templar imposed Magna Carta over the King of England in 1215 AD [23] [24], and even the King’s soldiers declined to resist them [25].

Therefore, the autonomous Franciscan Sacred Order, established in England of the early 13th century, unavoidably and necessarily, experienced close relations and strong cooperation with the influential Templar Order. These bonds were greatly strengthened by shared monastic missions, and by both Orders relying upon the Independent Church Movement for their security and future survival.

Most historians believe that Saint Francis personally attended the Fourth Lateran Council in Rome in 1215 AD [26], to support and ensure it confirming the Independent Church Movement as having Independent Bishops [27].

As a result, the Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi embraced the sacred mission of carrying the “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession, serving as the Guardians of Templar Sovereign Succession, managing those lines from its Synod of Independent Apostolic Clergy since 1221 AD.

Further confirming the Templar Franciscan bond, King Louis IX of France, of the Templar Angevin Royal House [28], was canonized in 1297 AD by Pope Boniface VIII (who was later kidnapped by King Philip IV who persecuted the Templars), specifically as a Patron Saint of the Franciscan Secular Orders [29].

King Louis IX, the Franciscan Patron Saint, accomplished distinctly Templar missions, as he reformed Justice, banned “trials by ordeal”, and established the legal “presumption of innocence”. He also outlawed all “usury”, banning any interest-bearing loans, making usurers compensate borrowers or pay all profits to the Crusades [30] [31], evidencing Templar Biblical banking principles.

Templar Mission of Saint Francis – The close cooperation of the Franciscan Sacred Order with the Templar Order, both based in England, is most compellingly evidenced by Saint Francis himself pursuing the Templar tradition of peace and friendship with the Sultanate of Salahadin.

With the Templar King Richard the Lionheart of England, the Knights Templar continually discovered religious common ground and mutual friendship with their Muslim counterparts of the Sultan Salahadin, even between battles [32] [33] [34], which led to the Treaty of Ramla between King Richard and Salahadin in 1192 AD [35] [36].

Only seven years after establishing the autonomous Franciscan Sacred Order in Templar England in 1212 AD, Saint Francis was evidently greatly inspired by this Templar legacy, and thus was determined to renew and preserve it.

In 1219 AD, Saint Francis with one other Friar traveled to meet with the Sultan Al-Kamil, King of Egypt (also called “Meledin”), the nephew and third successor of Salahadin. In the middle of battles of the Fifth Crusade in Egypt, Saint Francis arrived, intending to either convert the Sultan to Christianity, or earn martyrdom in his attempt. [37]

One 13th century chronicle recorded: “When the Sultan saw his enthusiasm and courage, he listened to [Francis] willingly and pressed him to stay” [38].

Vatican historians summarize the chronicles:

“Francis proceeded to preach the Gospel to the Sultan… The two Friars stayed in the Muslim camp for several days and departed on peaceful terms. … The encounter changed Al-Kamil, who… began to treat Christian prisoners of war with surprising kindness. The Sultan proceeded to negotiate for peace with the Crusaders.” [39]

This evangelical mission by Saint Francis himself directly resulted in the treaty from the Templar King Richard and Salahadin being restored and reconfirmed, by the Treaty of Acre between King Frederick II of Jerusalem and Salahadin’s successor Sultan Al-Kamil “Meledin” in 1229 AD [40].

As a result of these facts in the historical record, the chivalric missions and Sovereign Succession of the Templar Order, as well as the Templars themselves, actively survived through the 13th century Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi, as an autonomous Secular Franciscan Order for non-monastic Clergy and missionaries, directly continuing into the modern era.

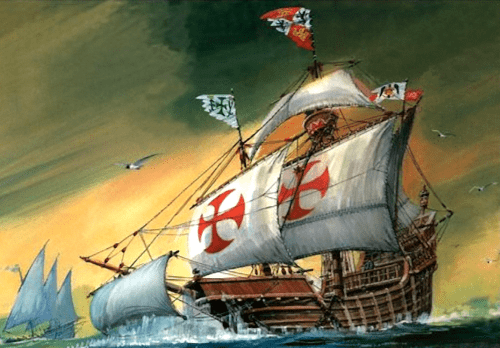

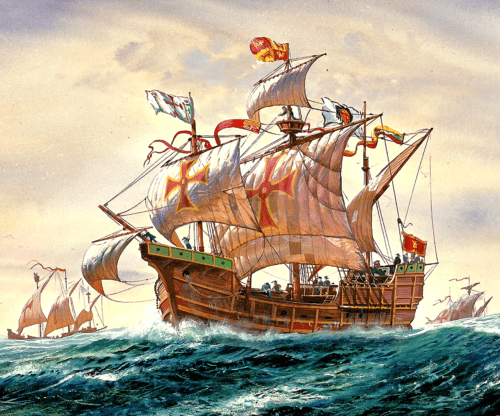

Most of the central working assets, equipment, documents and records of the Templar Order in France, together with the majority of its Knights and Dames, Sergeants and Adjutantes, supporters and their families, successfully escaped shortly before the infamous raids beginning the French Persecution.

Most of the central working assets, equipment, documents and records of the Templar Order in France, together with the majority of its Knights and Dames, Sergeants and Adjutantes, supporters and their families, successfully escaped shortly before the infamous raids beginning the French Persecution.

European historians established that there is “no doubt” that the Grand Mastery “was aware that the arrests were impending”, ordered for 13 October 1307 AD, while “the arrest orders were dated 14 September, so at the most the Templars had four weeks advance notice. … With a [purposely] depleted stockpile of workable assets… the Templars fled the area of immediate persecution before the hammer could fall.” [41]

The Templar trials recorded testimony of the Knight Jean de Châlon, who confirmed that the Order had advance warning of the impending raids, and had already arranged a fleet of 18 galleon ships to leave Port La Rochelle, visibly leaving behind a couple ships to avoid raising suspicions of their silent escape [42]:

The Templar trials recorded testimony of the Knight Jean de Châlon, who confirmed that the Order had advance warning of the impending raids, and had already arranged a fleet of 18 galleon ships to leave Port La Rochelle, visibly leaving behind a couple ships to avoid raising suspicions of their silent escape [42]:

This testimony specified that: “Gerard de Villiers, the Paris Preceptor, had escaped with 50 horses and 18 ships.” [43]

Templar Heroes Stayed Behind – The Temple Rule of 1129 AD commands self-sacrifice for one’s fellow Templars in times of peril:

“It is the truth… as if by a debt, that you must give your lives for your Brothers [and Sisters], just as did Jesus Christ” (Rule 56).

“That is: ‘I will avenge the death of Jesus Christ by my death. For just as Jesus Christ gave his body for me, I also am prepared in such manner to give my life for my Brothers [and Sisters]’. This is an appropriate offering, truly a living sacrifice and very pleasing to God.” (Rule 63) [44]

Precisely for this reason, for that purpose, and with this intent, the Grand Master Jacques de Molay with a group of dedicated Knights stayed behind, to avoid causing suspicion, thereby allowing the majority to escape to safety.

Relocating the Templar Order – As a result of this self-sacrifice, historians established that “Only 620 Templar personnel are known to have been arrested in France” in 1307 AD, and “estimate that there were over 3,000 Templars” in France, such that “over 2,000 fully armed and equipped Templar[s], with their entire retinues of squires, servants, horses, baggage trains and camp followers”, in fact did escape, and boarded the 18 ships which left Port La Rochelle [45].

European historians documented that “the Templars managed to disperse most of their portable wealth before the King’s henchmen came to confiscate it. Indeed, the royal agents found monasteries that had in large part been abandoned… [then] they found the ships had set sail”.

Other “Templar fleets in the south and north of France, Flanders, and Portugal also left port – and sailed into legend. … Also missing from the Templars’ strongholds were the documents and records” of the Order. [46]

For the Order to survive as an underground network, the Templars “fell back on their second career, finance and trade. … Most of the Templar wealth was out in the field earning interest and revenue for the Order… the money would be transferred to those branches still open and put to even greater use to recover the recent losses.”

In addition to the 18 ships which escaped from Port La Rochelle, “the vast majority of Templar ships, both merchant vessels and armed galleons… would surely have been doing what the Templars did best – plying [working] the seas of the Mediterranean and Atlantic, earning money to keep the Order financially sound.” [47]

Ancient Switzerland was essentially undeveloped and unorganized, consisting of tribal frontier regions, and only the Valais region became governed by the French Bishop of Burgundy in 999 AD [48]. With involvement of the Knights Templar, the first three Cantons of Switzerland were founded in 1291 AD. Swiss government historians documented that by 1300 AD, the Templar Order was prominently active in Switzerland, and established autonomy of the Valais region:

Ancient Switzerland was essentially undeveloped and unorganized, consisting of tribal frontier regions, and only the Valais region became governed by the French Bishop of Burgundy in 999 AD [48]. With involvement of the Knights Templar, the first three Cantons of Switzerland were founded in 1291 AD. Swiss government historians documented that by 1300 AD, the Templar Order was prominently active in Switzerland, and established autonomy of the Valais region:

“In 1260 AD… [Count] Peter II seized the castle of Martigny, [giving] access to the ‘Great Saint Bernard’, and forced the Bishop to yield to him… the Episcopal Valais [region]. … The recognition of his sovereign rights in 1293 AD and … under [Prince] Pierre IV of Tours in 1294-1299 AD reinforced the position of the ‘Prince Bishop’.” [49]

As the founding Templar Patron Saint Bernard de Clairvaux had already died in 1153 AD, this coded reference to the “Great Saint Bernard”, developing Swiss Valais as a Principality since 1260 AD, can only mean the Templar Order as a major world institution. Confirming this, the unusual “Prince Bishop” model of sovereign autonomy for Valais directly mirrors the distinctive “Prince Grand Master” model of sovereignty of the Templar Order [50] [51] [52] [53].

Therefore, when the French Persecution began in 1307 AD, the Templar Order had already completed at least seven years of actively preparing Switzerland to be a safe haven under a sovereign Prince Bishop, fully establishing a practical backup plan for any future escape and survival.

Therefore, when the French Persecution began in 1307 AD, the Templar Order had already completed at least seven years of actively preparing Switzerland to be a safe haven under a sovereign Prince Bishop, fully establishing a practical backup plan for any future escape and survival.

When the 18 galleon ships left Port La Rochelle in France, the Templars were able to sail north to the Netherlands of the Teutonic branch of the Order, to dock and keep their ships, and then travel south to Switzerland.

Relocation Also by Land Routes – In addition to the ships, as an easier and less noticeable escape route, even more of the Templars were able to travel by land, directly east to Switzerland. European historians confirmed:

“Trade routes to Northern Italy ran through the passes of Switzerland… paths regularly trodden by Templar traders… while [King] Philip’s attention was deliberately being focused on the West coast of France, anything of value that the Templars wished to preserve was being slowly and systematically transferred overland to the East. There were dozens of routes from France into the Alps” [54].

Indeed, on medieval maps, the Templar region of Valais is located on a major trade route in a direct line from Burgundy France to Milan Italy.

Niederrohrdorf 12th century Coat of Arms with Templar Agnus Dei

Templars Founded Swiss Nation – During the 13th century, “nothing like the present State of Switzerland even existed”, and it was mostly “a complex series of nominally independent dukedoms and fiefdoms”.

When the first Cantons formed in 1291 AD, “folk tales began to spread regarding the assistance that the new alliance received from white-clad Knights, whose vestments bore the familiar Red Cross of the Templars. … And the fact that tales of white-clad Knights assisting the first struggling Swiss Cantons preceded the events of 1307 AD surely [evidences] that the Templars began to take steps to ensure their own survival”. [55]

Swiss Flag from Templar Flag – The medieval Swiss city Nidern Rordorf since 1179 AD [56] has as its coat of arms the distinctive Templar “Agnus Dei” (Lamb of God) bearing the Templar Red Cross on a white flag [57], which comes from the official Templar Grand Mastery Seal used in England (since 1160 AD) [58]. This evidences the Templar origins of the Swiss national flag, as established by European historians:

“It is no coincidence… that the very flag of Swiss nationhood is simply a reversed version of the most famous Templar motif, for instead of being a Red Cross on a white field, it is a white cross on a red field. Research into the origins of the Swiss flag revealed… the folk tales of white-clad Knights fighting bloody battles for the fledgling confederation.”

“[Thus] the very flag of this neutral nation of Switzerland is none other than a representation of… those Templars who fought for the freedom of the embryonic Swiss nation.” [59]

“[Thus] the very flag of this neutral nation of Switzerland is none other than a representation of… those Templars who fought for the freedom of the embryonic Swiss nation.” [59]

The reversal of Templar colours for the Swiss flag is also from the Templar galleon ships which escaped from France and abandoned other parts of Europe to relocate to Switzerland.

Different from the flag of the Templar Principality which is half black on the top, the Templar ships for practical reasons had entirely white sails, marked only with a Red Cross.

In customary heraldic law of State flags, this reversal of flag colours symbolizes the reversal of Templar support for France, and the reversal of Templar public missions to serve as an underground network, through establishing the modern country of Switzerland.

Swiss Neutrality for Templar Survival – The Templar Order had to escape the French Persecution of 1307 AD, which was driven exclusively by corrupt politics of secular States. It then activated its survival plans to relocate mostly to Switzerland, to finish developing and establishing it as an independent Templar State capable of protecting their human rights.

As a result, political “Neutrality” became the most pressing necessity, as a strategic policy to ensure survival of the Templar Order. The Knights Templar thus made geopolitical neutrality the essential foundational policy of Switzerland, to protect it as an emerging Templar State. Therefore, the famous principle of strict political “Swiss Neutrality” is a distinctive trademark of the surviving Templar Order.

European historians documented: “Switzerland as a whole became synonymous with the ‘right to personally held beliefs’. … Switzerland remains almost pathological in its Quest for Neutrality… Switzerland represents exactly what a Templar State would have been destined to become… Underlying the whole Swiss experiment is the search for an equitable, democratic society, where each individual retains an importance to the whole, no matter what the language, political beliefs or religious persuasion of that person might be.” [60]

Rescue Dog Named “Saint Bernard” – Further reflecting the Templar foundations of Switzerland as a Templar State for survival of the Order, the iconic and legendary Swiss national rescue dog is named the “Saint Bernard”. This faithful dog is evidently dedicated to the Templar Patron Saint Bernard de Clairvaux (canonized 1174 AD), who established and implemented survival plans with Popes and Bishops as Templar loyalists.

During the Middle Ages, “Saint Bernard” dogs were originally called “Alpine Mastiffs”, named after the “Alpine Pass”, the same major trade route through Switzerland (between France and Italy) extensively used for centuries by the Knights Templar.

Although a previous “Saint Bernard of Menthon” (1020-1081 AD) founded a monastery and traveler shelter at the highest peak of the Alpine Pass ca. 1045 AD, he was not canonized as a Saint until 1681 AD, that monastery did not use dogs until 1707 AD, and dog rescues were not reported until 1800 AD.

The Alpine Mastiffs were officially named “Saint Bernards” by the Swiss Kennel Club in 1880 AD [61], and officially recognized as the “Swiss National Dog” in 1887 AD [62].

The Monk Bernard of Menthon was not declared the Patron Saint of the Alps until the modern era in 1923 AD [63]. In contrast, the historical record evidences that since 1260 AD, and thus throughout the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, the Templar Order was already widely known in Switzerland by the affectionate nickname of “The Great Saint Bernard” [64].

A national mascot must reflect the founding heritage of the nation, such that the Swiss mascot must have been named after the Templar foundations and underlying Templar heritage of Switzerland, which led the Swiss nation out of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. It is thus most logical and probable, that the “Saint Bernard” dogs were actually named after the 12th century Templar Patron Saint Bernard de Clairvaux.

Modern Swiss Templar Culture – Modern Switzerland was first recognized as a sovereign country, with declared geopolitical neutrality, by the Treaties of Westphalia in 1648 AD. It was a founding Member State of the League of Nations in 1920 AD, and became a full Member State of the modern United Nations only as late as 2002 AD.

Expressing the traditional Knights Templar principles and culture from its medieval foundations, and reflecting the Templar Order continuing into the modern era, Switzerland is the birthplace of the international Red Cross medical charity, which originated in Geneva in 1863 AD, and expanded as the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement since 1919 AD.

The Knights Templar first established their influence in Scotland in 1128 AD, when the Angevin King Henry I of England arranged the introduction of the first Templar Grand Master Hughes de Payens to King David I of Scotland. King David granted the Templar Order its headquarters and Preceptory of Balintradoch in 1129 AD, later renamed the town of “Temple” in Midlothian, located seven kilometers from Rosslyn.

The Knights Templar first established their influence in Scotland in 1128 AD, when the Angevin King Henry I of England arranged the introduction of the first Templar Grand Master Hughes de Payens to King David I of Scotland. King David granted the Templar Order its headquarters and Preceptory of Balintradoch in 1129 AD, later renamed the town of “Temple” in Midlothian, located seven kilometers from Rosslyn.

Soon the Knights Templar were landlords owning over 500 sites in Scotland. Evidencing recognition as a sovereign non-territorial Principality in its own right, the Templar Order, and even tenants on its lands, were exempt from all tithes and taxes, and also from all courts or jury duty. [65]

King David I of Scots appointed the Templars as “the Guardians of his morals by day and night”, establishing a strong tradition of the Knights Templar serving as Royal Advisors to all Scottish Kings. [66]

Robert the Bruce Supported Templars

King Robert I of Scots, “Robert the Bruce”, the 4th great grandson of King David I, led the First War of Scottish Independence against invading England.

Robert I ‘The Bruce’ and his wife Isabella, in ‘Forman Armorial’ (1562 AD), produced for Mary Queen of Scots, in National Library of Scotland (Detail)

In 1306 AD, Robert the Bruce was excommunicated by Pope Clement V for killing his rival John “the Red” Comyn during his accession to the throne. This made him sympathetic to the Templar Order during the French Persecution of 1307 AD, and gave him personal motivations to give the Templars refuge and an active role in defending Scotland. [67] [68] [69]

European historians documented: “There is much to indicate that Robert the Bruce [held] more than a passing interest in Templarism… he had strong Templar and Crusader leanings; so much so, that at his death he had left instructions that his heart should be taken on Crusade and buried in Jerusalem.” [70]

In 1308 AD, giving in to French pressure, King Edward II of England arrested only a few dozen Templars, allowed limited Templar trials during only one year from 1309-1310 AD (which included the Temple Preceptory in Scotland), and all Templars were acquitted and released. In 1312 AD, however, Edward II adopted the Papal Bull Vox in Excelso, and thus “suppressed” the Templar Order in both England and Scotland.

However, as Robert the Bruce was already purportedly excommunicated by the Pope, and was determined to support the Knights Templar, he did not allow any trials nor suppression in the territories directly controlled by Scotland.

Templars Supported Robert the Bruce

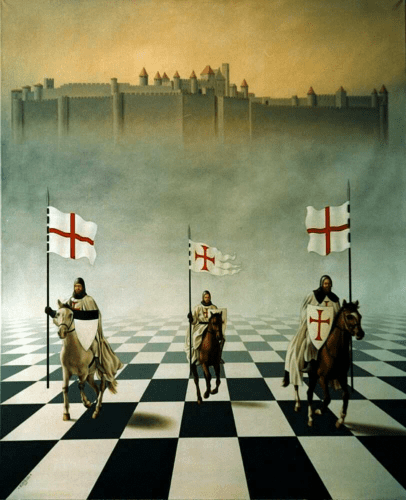

In 1314 AD, seven years after the French Persecution of the Knights Templar, and two years after the Vatican’s “suppression” of the Order, Robert the Bruce famously sent the English army “hameward tae think again”, at the Battle of Bannockburn, which primarily won the War of Scottish Independence.

An American lawyer and Scottish historian established by “statistical analysis” that more Templars also arrived from France and other parts of Europe, with “at least 335 avoiding capture” by fleeing to Scotland.

In addition to numerous Templars already in Scotland, the arriving Templars included “at least 29 battle-hardened Knights and Sergeants… as [many] as 48 [Templars]”. The research concluded: “Given the battle plan… for Bannockburn… the Templars were necessary… The existence of Templars at Bannockburn follows a consistent line of facts.” [71]

Historians have documented 14th century accounts in the historical record, evidencing active Templar military support of Robert the Bruce:

Historians have documented 14th century accounts in the historical record, evidencing active Templar military support of Robert the Bruce:

“Templar forces reportedly fought alongside the King in 1314 at the Battle of Bannockburn… Contemporary chroniclers maintained that the superior military skills of the Templars tipped the battle in Bruce’s favor”.

“According to legend, despite their superior numbers, the English forces fled the field when the Templars seemed to appear out of nowhere, charging from the hidden rear of the regular Scottish troops. The image of the Templars, with their white tunic and Red Cross, looked as though the ghosts of the long ago Crusades had suddenly materialized to provide miraculous assistance to the outnumbered Scots. Although his troops were actually winning the battle, the English King, Edward II, retreated in terror upon seeing these ghostly apparitions”. [72]

Direct lines of successive generations of initiatory cultural and chivalric Templars survived into the modern era, preserving and continuing the original Templar missions. In addition to the immediate and primary survival plan originally established by Saint Bernard, during the decades after the French Persecution, living Templars and their descendants continued Templar Chivalry through joining several other Orders.

Direct lines of successive generations of initiatory cultural and chivalric Templars survived into the modern era, preserving and continuing the original Templar missions. In addition to the immediate and primary survival plan originally established by Saint Bernard, during the decades after the French Persecution, living Templars and their descendants continued Templar Chivalry through joining several other Orders.

Specifically, surviving Templars joined the following Orders (indicating dates of joining, with date range of continuation):

Franciscan Sacred Order in England (1307-present), Franciscan Vatican Order (1307-present), Ancient Celtic Churches (1307-present), German Teutonic Order (1312-1929), Spanish Montesa Order (1317-1587), Portuguese Knights of Christ (1319-1789), and Rosicrucian Mystical Order (1407-present).

Franciscan Sacred Order – The surviving Knights Templar in England and Western Europe successfully followed the survival plan established by Saint Bernard, and pre-arranged with the Franciscan Sacred Order:

Franciscan Sacred Order – The surviving Knights Templar in England and Western Europe successfully followed the survival plan established by Saint Bernard, and pre-arranged with the Franciscan Sacred Order:

The Templar Order primarily continued through the “Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi”, established in England in 1212 AD, which was already dedicated to that purpose as a “Secular Franciscan Order” since 1221 AD, as Guardians of the “Templar Lines” of Sovereign Succession through the Independent Church Movement [73].

When the French Persecution began 86 years later in 1307 AD, nothing further needed to be done, and the Templars simply traded their chivalric tunics for Franciscan brown monastic robes. “Mission Accomplished”.

In 1520 AD Pope Leo X, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival through the Franciscan Sacred Order by expanding the Independent Church Movement, granting the Papal Bull Debitum Pastoralis to the Bishop of Utrecht, who was a Teutonic Knight promoting surviving Templarism [74].

Franciscan Vatican Order – From 1307-1312 AD, many Templars throughout Western Europe either joined the autonomous Franciscan Sacred Order in England, or it facilitated to arrange them joining the Franciscan “Tertiary (Secular) Order” of the Vatican, somewhat analogous to the role of Knights and Dames.

Franciscan Vatican Order – From 1307-1312 AD, many Templars throughout Western Europe either joined the autonomous Franciscan Sacred Order in England, or it facilitated to arrange them joining the Franciscan “Tertiary (Secular) Order” of the Vatican, somewhat analogous to the role of Knights and Dames.

However, the Vatican Franciscan Order does not carry the “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession which are unique to the independent Anglican Sacred Order.

As a purely monastic Order, it does not grant knighthood or damehood. The modern Tertiary Order under the Vatican has almost 600 Clergy and 300 Secular members [75].

Ancient Celtic Churches – From 1307-1312 AD, many Templars in Scotland, Ireland, and throughout Western Europe joined Ancient Celtic Churches within the Independent Church Movement (founded 1145 AD).

These Celtic Churches originated from Ancient Celtic Priesthoods of England, Scotland and Ireland, which became an Apostolic “Celtic Catholic” line (from Saint Mark in 336 AD, through Saint Silverius in 536 AD, and Saint Nicholas I in 858 AD), and “Celtic Anglican” line (from Saint David, first Celtic Bishop of Mineva in Wales in 519 AD, through Celtic Archbishops of Canterbury).

These Celtic Churches originated from Ancient Celtic Priesthoods of England, Scotland and Ireland, which became an Apostolic “Celtic Catholic” line (from Saint Mark in 336 AD, through Saint Silverius in 536 AD, and Saint Nicholas I in 858 AD), and “Celtic Anglican” line (from Saint David, first Celtic Bishop of Mineva in Wales in 519 AD, through Celtic Archbishops of Canterbury).

In 1520 AD Pope Leo X, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival through the Ancient Celtic Churches by expanding the Independent Church Movement, granting the Papal Bull Debitum Pastoralis to the Bishop of Utrecht, who was a Teutonic Knight promoting surviving Templarism [76].

As individual autonomous Churches, not yet consolidated to act collectively through a unified independent Sovereign Pontificate established under Canon law in customary law, they could not create any Orders of Chivalry [77] [78] [79], and thus could not grant nor arrange knighthood or damehood.

Teutonic Vatican Order – Starting in 1312 AD, many Templars in Germany or Eastern Europe joined the Order of Teutonic Knights of the Vatican (founded 1190 AD), which was already an official but autonomous branch of the Templar Order [80] [81].

Teutonic Vatican Order – Starting in 1312 AD, many Templars in Germany or Eastern Europe joined the Order of Teutonic Knights of the Vatican (founded 1190 AD), which was already an official but autonomous branch of the Templar Order [80] [81].

The Teutonic Order continued as such for 739 years, until it was “reformed” in 1929, “re-established” in 1957, and “restructured” in 1965, becoming the “Order of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem”. The modern Order of Mary has about 300 Clergy and 700 secular “Familiares” in a role analogous to Knights [82], but does not grant knighthood or damehood.

Surviving Templars from the Teutonic Order, after 1929, joined the Franciscan Sacred Order in England, Franciscan Vatican Order, Ancient Celtic Churches, or Rosicrucian Mystical Order (all continued to the present day).

Spanish Montesa Order – In 1317 AD, King James II of Spain “obtained from Pope John XXII… the possessions of the Templars in his Kingdom”, to create the “Military Order of Montesa… established… to take the place of the Order of the Temple… [as] the continuation.” The Order of Montesa was placed under the Cistercian Rule, and based upon the Templar Order. [83]

Spanish Montesa Order – In 1317 AD, King James II of Spain “obtained from Pope John XXII… the possessions of the Templars in his Kingdom”, to create the “Military Order of Montesa… established… to take the place of the Order of the Temple… [as] the continuation.” The Order of Montesa was placed under the Cistercian Rule, and based upon the Templar Order. [83]

Thus in 1317 AD, Pope John XXII, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival through the Order of Montessa by granting it Vatican Patronage.

Starting in 1317 AD, many Templars in Spain or Western Europe joined the Order of Montesa.

The Order of Montesa (from 1317 AD) operated for 270 years, until it was “united with the Crown” in 1587 AD, thereby dissolving it [84].

Surviving Templars from the Order of Montesa, after 1587 AD, joined the German Teutonic Order (until 1929), Portuguese Knights of Christ (until 1789), or joined the Franciscan Sacred Order in England, Franciscan Vatican Order, Ancient Celtic Churches, or Rosicrucian Mystical Order (continued to the present day).

Portugal Knights of Christ – In 1319 AD, in Portugal the Knights Templar were cleared of all charges, and Pope John XXII, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival by merely renaming the Portuguese branch of the Order to “Knights of Christ”, allowing to keep their assets.

Portugal Knights of Christ – In 1319 AD, in Portugal the Knights Templar were cleared of all charges, and Pope John XXII, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival by merely renaming the Portuguese branch of the Order to “Knights of Christ”, allowing to keep their assets.

Starting in 1319 AD, many Templars in Portugal or Western Europe joined the Knights of Christ.

In 1740 AD Pope Benedict XIV, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival as the “Knights of Christ” by granting the former headquarters of the Knights Templar to the King of Portugal for the renamed Order.

The Knights of Christ (from 1319 AD) operated for 470 years, until it was dismantled in 1789 AD: It was reduced to an “honourary decoration of merit” by Queen Maria I in 1789 AD, fully “extinguished” with the end of the Portuguese Monarchy in 1910 AD, and later “reformulated” and “reinstated” in 1918 only as an “honorary award” under the President of the modern Republic of Portugal [85] [86].

A doctrine of customary international law holds that a “new government” of a modern secular “Republican State” does not have legal capacity of “rights of Fons Honourum” for the “exercise of heraldic jurisdiction” to maintain, revive nor even recognize Orders of Chivalry [87] [88] [89] [90]. Therefore, the modern Knights of Christ is not an Order of Chivalry, and thus does not grant knighthood or damehood.

Surviving Templars from the Knights of Christ, after 1789 AD, joined the German Teutonic Order (until 1929), or joined the Franciscan Sacred Order in England, Franciscan Vatican Order, Ancient Celtic Churches, or Rosicrucian Mystical Order (continued to the present day).

Rosicrucian Mystical Order – In ca. 1407 AD, the surviving Knights Templar in Portugal (renamed “Order of Christ” since 1319 AD) helped establish the Rosicrucian Order, named after the trademark Templar Red Cross, or “Rose Cross”, thus “Rosa-Cruz” (Portugese) or “Rossi-Croce” (Italian).

This is evidenced by the fact that the Portuguese Templar headquarters, the “Convent of the Order of Christ”, features three artifacts of a Rose at the center of a Cross in the initiation room, dated ca. 1530 AD [91] [92]. This establishes that many surviving Templars helped create and develop the Rosicrucian Order from 1407-1530 AD.

Starting in 1407 AD, and even more after 1530 AD, many Templars throughout Western Europe joined the Rosicrucian Mystical Order.

In 1740 AD Pope Benedict XIV, a Templar revivalist, supported Templar survival through the Rosicrucian Order by restoring “Templar Rosicrucian” lines of Apostolic Succession, “reinstating” those lines in the Vatican [93], and also by establishing the first Vatican “Academy of Antiquities” [94] to continue the Templar mission of exploring ancient origins of Christianity.

The Rosicrucian Order, as an esoteric society, was never established with sovereign authority, and thus by customary international law, it is not an Order of Chivalry [95], and thus does not grant knighthood or damehood.

Results Through Other Orders – In the end result, Templars from the original Order of the Temple of Solomon survived through other Orders, actively continuing Templar missions and living the Templar life of Chivalry, directly into the modern era.

After the other Orders of Chivalry which could grant knighthood and damehood ended, in 1587 AD (Spain), 1789 AD (Portugal) and 1929 AD (Germany), surviving Templars continued Templar missions through the Franciscan Sacred Order, Franciscan Vatican Order, Ancient Celtic Churches, and Rosicrucian Mystical Order.

After the other Orders of Chivalry which could grant knighthood and damehood ended, in 1587 AD (Spain), 1789 AD (Portugal) and 1929 AD (Germany), surviving Templars continued Templar missions through the Franciscan Sacred Order, Franciscan Vatican Order, Ancient Celtic Churches, and Rosicrucian Mystical Order.

However, none of these remaining institutions of Templar survival were Orders of Chivalry, and thus could not grant knighthood or damehood.

Also, only the Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi in England (since 1212 AD) preserved and carried the rights of Templar Sovereign Succession, through the rare and unique “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession.

Therefore, from 2007-2013, the Franciscan Sacred Order completed the original plan from Saint Bernard, by reunification with surviving cultural and chivalric Templars from Ancient Celtic and Rosicrucian branches of the Old Catholic Churches, to restore and reestablish the Templar Order to full legitimacy.

(See details of Legal Succession of the Templar Order)

Learn about the Foundations of the Order for its restoration.

Learn about the French Persecution suppressing the Order.

Learn about Templar Legal Succession continuing sovereignty.

[1] Michael Lamy, Les Templiers: Ces Grand Seigneurs aux Blancs Manteaux, Auberon (1994), Bordeaux (1997), p.28.

[2] Judith M. Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars, Woodbridge, The Boydell Press (1992), p.11; Dissertation for Master of Philosophy at Reading University.

[3] Michael Horn, Studien zur Geschichte Papst Eugens III (1145-1153), Peter Lang Verlag (1992), pp.36-40, pp.42-45.

[4] Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, On Consideration, Letter to Pope Eugene III, Translated in: George Lewis, Saint Bernard: On Consideration, Oxford Library of Translations, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1908).

[5] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.542.

[6] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.541.

[7] The Vatican, The Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), Translation in: H.J. Schroeder, Disciplinary Decrees of the General Councils, B. Herder, Saint Louis (1937), pp.236-296.

[8] Grand Mastery, Temple Rule of 1129 AD, Order of the Temple of Solomon (Amended ca. 1150 AD); Judith M. Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars, Woodbridge, The Boydell Press (1992); Grand Mastery continues through successive “Grand Commanders” serving “in place of the Grand Master” (Rule 204), until it is restored by “election of the Grand Master” by “the most prominent” Commanders (Rule 206).

[9] Grand Magistry, Constitutional Charter, Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), based on rules from ca. 1099 AD, Rome (Amended 1961); “The Grand Master is elected… from among the Professed Knights” (Article 13.1). During abeyance “the Order is governed by a Lieutenant ad interim in the person of the Grand Commander”, and the “Grand Magistry” continues through successive Lieutenants until restored by election (Article 17).

[10] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), pp.40, 47, 416; “uncorrupted historical and traditional link with the original Order… [as] historical roots or lineage”.

[11] François Velde, Legitimacy and Orders of Knighthood, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), Section I, Part B-1, “Historical Continuity: Military-Monastic Orders”; “Orders of knighthood… continue to exist [through] membership… following the original set of rules… [as] historical continuity”.

[12] The Vatican, The Code of Canon Law: Apostolic Constitution, Second Ecumenical Council (“Vatican II”), Enacted (1965), Amended and ratified by Pope John Paul II, Holy See of Rome (1983), Canon 120, §2; An Order “survives” as succession “of all the rights… devolves upon [any] member” continuing the authorized lineage in service of its original missions.

[13] Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See: A Historical, Juridical and Practical Compendium (1983), p.119.

[14] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), pp.291-292.

[15] François Velde, Legitimacy and Orders of Knighthood, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), Section I, Part C, “Conclusion”.

[16] The Vatican, The Code of Canon Law: Apostolic Constitution, Second Ecumenical Council (“Vatican II”), Enacted (1965), Amended and ratified by Pope John Paul II, Holy See of Rome (1983), Canon 120, §2; Canon 123; “arrangements for… rights… devolve upon the next higher [institution]”.

[17] Ancient Pontificate, Charter of Reestablishment and Reunification, Synod of Churches of Independent Church Movement of 1145 AD and Old Catholic Movement of 1870 AD, Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi from 1212 AD (Enacted 13 March 2013); Issued by five Franciscan Vatican Bishops; Article II “Representative Synod”, in Section “Franciscan Order”, p.4.

[18] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 6, “Friars Minor”, Part IV.

[19] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 6, “Friars Minor”, Part II: “Great Britain”.

[20] Ancient Pontificate, Charter of Reestablishment and Reunification, Synod of Churches of Independent Church Movement of 1145 AD and Old Catholic Movement of 1870 AD, Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi from 1212 AD (Enacted 13 March 2013); Issued by five Franciscan Vatican Bishops; Article II “Representative Synod” (top of list), and Section “Franciscan Order”, p.4.

[21] John Baker, Inner Temple History, Inner Temple (2009), Introduction, Part 1.

[22] James Campbell, The Map of Early Modern London: Chancery Lane, University of Victoria (2009).

[23] T.F. Tout, “Fitzwalter, Robert” in Leslie Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography (1889), London, Smith Elder & Co., p.226.

[24] Gabriel Ronay, The Tartar Khan’s Englishman, London, Cassel (1978), pp.38-40.

[25] T.F. Tout, “Fitzwalter, Robert” in Leslie Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography (1889), London, Smith Elder & Co., p.226.

[26] Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Saint Francis of Assisi, 14th Edition, Image Books, New York (1924), p.126.

[27] The Vatican, The Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), Translation in: H.J. Schroeder, Disciplinary Decrees of the General Councils, B. Herder, Saint Louis (1937), pp.236-296; Confirming “independent” Churches (Canon 5) as autonomous “cathedral churches” (Canons 10-11), with Independent Bishops (Canon 23), recognizing “ancient privileges” of “their [own] jurisdiction” (Canon 5).

[28] The younger brother of King Louis IX was Charles I of Anjou (1227-1285 AD), founder of the Second House of Anjou of the Royal Capetian Dynasty.

[29] Capuchin Mission Office, Saint Louis IX: King, Patron of the Secular Franciscans, “Capdox” Archives, Capuchin Franciscan Friars Australia (2015), Section “Saints and Blessed”.

[30] Lives of Saints, Saint Louis: Confessor King of France, Eternal World Television Network “EWTN”, Global Catholic Network, Alabama (1999), Archive “Catholicism: Library”, Section “Faith: Mary and Saints”.

[31] Father Joseph Vann (Editor), Lives of Saints: Selected and Illustrated, Guttenberg Edition, John J. Crawley & Co., New York (1954), “Saint Louis IX”.

[32] Malcolm Cameron Lyons & D.E.P. Jackson, Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War, University of Cambridge Oriental Publications (Book 30), 1st Edition, Cambridge University Press (1982), based on Arabic medieval manuscript sources, p.357.

[33] Charles J. Rosebault, Saladin: Prince of Chivalry, Robert M McBride & Co, New York (1930), Chapter 1, “The Knighting of Saladin”, pp.1-3.

[34] Pir Zia Inayat-Khan, Saracen Chivalry: Counsels on Valor, Generosity and the Mystical Quest, Suluk Press, Omega Publications, New Lebanon New York (2012), Introduction, p.xi.

[35] Facts on File Library of World History, Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, Africa (2009), “Saladin”, p.386.

[36] J. Gordon Melton, Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History, ABC-CLIO Publishing (2014), “1192”, “September 2, 1192”, p.786.

[37] John V. Tolan, Saint Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter, Oxford University Press (2009).

[38] Bonaventure, Legenda Ancti Francisci”, “Legenda Major” (1260 AD), Chapter IX, §§7-9; Cardinal Manning, Bonaventure: The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi, 1st Edition (1867), TAN Books, Illinois (1988); John V. Tolan, Saint Francis and the Sultan, Oxford University Press (2009), p.168.

[39] Philip Kosloski, St. Francis and the Sultan: An Encounter of Peace, Journal “Aleteia”, in Communion with Vatican, supported by Pontifical Council for Social Communications, Aleteia SAS, Paris (28 June 2017).

[40] Joseph W. Meri & Jeri L. Bacharach, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Taylor and Francis (2006), p.84.

[41] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), p.23.

[42] Heinrich Finke, Papsttum und Untergang des Templerordens, Munster: Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchh (1907), pp.338-339.

[43] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), p.25.

[44] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 269.

[45] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.26, 30-31.

[46] Frank Sanello, The Knights Templars: God’s Warriors, the Devil’s Bankers, Taylor Trade Publishing, Oxford (2003), p.201.

[47] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.23-24, p.29.

[48] Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Cambridge University Press (1911), “Valais”.

[49] Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse, “Historical Dictionary of Switzerland” (French Edition), Editions Gilles Attinger & Swiss Historical Society (2014), Article: “Sion (évêché)” (Bishopric of Sion).

[50] Saint Michael Academy of Eschatology, The Chivalry: Classification of the Orders, West Palm Beach, Florida (2008), updated (2015), Free Course No.555: “Chivalric Orders”, Lesson 3, Part 2.

[51] Noel Cox, The Sovereign Authority for the Creation of Orders of Chivalry, “Arma” Journal, Heraldry Society of Southern Africa (1999-2000), pp.317-329.

[52] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.294.

[53] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.542.

[54] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.88-89.

[55] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.86-87.

[56] Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse, “Historical Dictionary of Switzerland” (French Edition), Editions Gilles Attinger & Swiss Historical Society (2014), Article: “Niederrohrdorf”.

[57] Wappen von Niederrohrdorf, “Coat of Arms of Niederrohrdorf”, Das Staatsarchiv Aargau (Aargau State Archive), Wappenregister Aargau No.1-4.

[58] Charles G. Addison, The History of the Knights Templars, Longman Brown & Green, London (1842), Preface, p.xi.

[59] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.91-92.

[60] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), pp.93-94.

[61] Wayne Curtis, The Myth of the St. Bernard & the Brandy Barrel, The Daily Beast (05 February 2018).

[62] Kashyap Dave, St. Bernard: Dog Breed Information and Facts, “Dog Lover” Magazine, India (2018), Section “Origin & History”.

[63] Thomas Craughwell, A Patron Saint for Mountain Climbers, The Arlington Catholic Herald (19 May 2005).

[64] Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse, “Historical Dictionary of Switzerland” (French Edition), Editions Gilles Attinger & Swiss Historical Society (2014), Article: “Sion (évêché)” (Bishopric of Sion).

[65] C. Robert Ferguson, Esq., The Knights Templar and Scotland, 1st Edition, The History Press, Glaucestershire (2010), 2nd Edition (2013); Excerpts in: The Knights Templar and Scotland, “History Scotland” Magazine (23 May 2013); Robert Ferguson is an American lawyer, and former Vice President of the Scottish Clan Ferguson Society; His book was endorsed by Raymond Morris, Laird of 14th century Balgonie Castle in Fife.

[66] Philip Coppens, The Stone Puzzle of Rosslyn Chapel, 1st Edition, Frontier Publishing (2004), 2nd Edition, Adventures Unlimited Press (2015); Philip Coppens is an investigative journalist and historical researcher, often featured in documentary films on the History Channel.

[67] Gordon Napier, A to Z of the Knights Templar, Spellmount Limited, Gloucestershire (2008).

[68] Troy Depue, Templars and Robert the Bruce, Medieval Facts Examiner, Texas (10 November 2017); Troy Depue is a published journalist for the UK “Examiner” Newspaper, featured on the Travel Channel and NPR radio.

[69] C. Robert Ferguson, Esq., The Knights Templar and Scotland, 1st Edition, The History Press, Glaucestershire (2010), 2nd Edition (2013); Excerpts in: The Knights Templar and Scotland, “History Scotland” Magazine (23 May 2013).

[70] Alan Butler and Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and the Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), p.34.

[71] C. Robert Ferguson, Esq., The Knights Templar and Scotland, 1st Edition, The History Press, Glaucestershire (2010), 2nd Edition (2013); Excerpts in: How Crusading Templars Gave Bruce the Ege at Bannockburn, “The Scotsman” Newspaper (05 December 2009); Robert Ferguson is an American lawyer, and former Vice President of the Scottish Clan Ferguson Society; His book was endorsed by Raymond Morris, Laird of 14th century Balgonie Castle in Fife.

[72] Frank Sanello, The Knights Templars: God’s Warriors, the Devil’s Bankers, Taylor Trade Publishing, Oxford (2003), p.202.

[73] Ancient Pontificate, Charter of Reestablishment and Reunification, Synod of Churches of Independent Church Movement of 1145 AD and Old Catholic Movement of 1870 AD, Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi from 1212 AD (Enacted 13 March 2013); Issued by five Franciscan Vatican Bishops: Archbishop Mar Frederick, Cardinal Bruce D. Campbell, Archbishop Benjamin B. Driggers, Archbishop David L. Rochelle, Cardinal Peter R. Edwards; Article II “Representative Synod”, in Section “Franciscan Order”, p.4.

[74] Louis Sicking, Zeemacht en Onmacht: Maritieme Politiek in de Nederlanden 1488-1558, De Bataafse Leeuw, Amsterdam (1998).

[75] The Vatican, Annuario Pontificio, Liberia Editrice Vaticana (2013), p.1422.

[76] Louis Sicking, Zeemacht en Onmacht: Maritieme Politiek in de Nederlanden 1488-1558, De Bataafse Leeuw, Amsterdam (1998).

[77] Saint Michael Academy of Eschatology, The Chivalry – Classification of the Orders, West Palm Beach, Florida (2008), updated (2015), Free Course No.555: “Chivalric Orders”, Lesson 3, Part 2.

[78] Vatican, Official Statement of the Holy See on Self-Styled Orders, l’Osservatore Romano (1953), Republished (1970), translated in: Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, Orders of Knighthood Awards and the Holy See: A Historical, Juridical and Practical Compendium (1983).

[79] Saint Michael Academy of Eschatology, The Independent Orders vis a vis the Holy See, West Palm Beach, Florida (2008), updated (2015), Free Course No.555: “Chivalric Orders”, Lesson 3, Part 4.

[80] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.542.

[81] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.541.

[82] William Urban, The Teutonic Knights: A Military History, Greenhill Books, London (2003), p.277

[83] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 10, “Military Order of Montesa”.

[84] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 10, “Military Order of Montesa”.

[85] Republic of Portugal, Antigas Ordens Militares (“Old Military Orders”), Ordens Honorificas Portuguesas (“Portuguese Honorific Orders”), Presidential Administration of the Republic of Portugal (2011).

[86] Olimpio de Melo, Portuguese Military Orders and other Decorations, National Press, Lisbon (1922), p.31.

[87] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.415.

[88] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 5.

[89] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.416.

[90] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 2.

[91] Antonio de Macedo, Instruções Iniciáticas – Ensaios Espirituais, 2nd Edition, Hughin Editores, Lisbon (2000), p.55.

[92] J. Manuel Gandra, Portugal Misterioso: Os Templários, Lisbon (2000), pp.348-349.

[93] Ancient Pontificate, Charter of Reestablishment and Reunification, Synod of Churches of Independent Church Movement of 1145 AD and Old Catholic Movement of 1870 AD, Sacred Order of Saint Francis of Assisi from 1212 AD (Enacted 13 March 2013); Issued by five Franciscan Vatican Bishops: Archbishop Mar Frederick, Cardinal Bruce D. Campbell, Archbishop Benjamin B. Driggers, Archbishop David L. Rochelle, Cardinal Peter R. Edwards; Article VII “Templar Restoration”, p.12.

[94] The Vatican, Pontifical Roman Academy of Archaeology, Pontifical Council for Culture, Rome, Online: Theologia.va (July 2012).

[95] François Velde, Legitimacy and Orders of Knighthood, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), Section III, “Legal Definitions of Orders of Knighthood”.

You cannot copy content of this page