Official regalia of the modern Templar Order, authentic to 12th century traditions, following 14th century Rules as the international standard. Timeless and regal, yet modest, tasteful, practical and versatile.

By definition, the Latin word ‘Regalia’ means official clothing and insignia characteristic of Nobility and Chivalry under a Sovereign, and by 1670 AD it came to mean specifically the dress and insignia of a chivalric Order [1]. Regalia is an ancient tradition continued through medieval chivalric institutions, communicating their official status and public role within an international system.

By definition, the Latin word ‘Regalia’ means official clothing and insignia characteristic of Nobility and Chivalry under a Sovereign, and by 1670 AD it came to mean specifically the dress and insignia of a chivalric Order [1]. Regalia is an ancient tradition continued through medieval chivalric institutions, communicating their official status and public role within an international system.

The primary purpose of regalia is for all members and officials of a historical institution wearing it to be reminded of the profound responsibilities which their traditions have entrusted to them.

Regalia is a timeless tradition based upon conventional protocols, used for practical purposes, as uniforms properly identifying a chivalric Order or sovereign institution in official or diplomatic relations. It is also used to communicate the religious character of an Order in the context of ecclesiastical worship and sacraments.

Many private fraternities in the modern era make prominent use of decorative regalia, to give their membership activities a traditional atmosphere. The popularized ceremonial trappings widely used by self-styled revival groups, generally attributed to the “Knights Templar”, are not authentic to the 12th century Order of the Temple of Solomon.

Many private fraternities in the modern era make prominent use of decorative regalia, to give their membership activities a traditional atmosphere. The popularized ceremonial trappings widely used by self-styled revival groups, generally attributed to the “Knights Templar”, are not authentic to the 12th century Order of the Temple of Solomon.

The typical long white robes with large red crosses, and other related accessories, were actually invented by the 15th century fraternity of Freemasonry (which is not an Order of Chivalry, and correctly does not claim to be). The Masonic “Templar” styled regalia was intended only for private ceremonial use as a fraternity [2]. Accordingly, such regalia is only authentic to Freemasonry, and not to historical Templarism.

The regalia of the original Templar Order was never meant to be decorative nor grandiose, but was always designed to be purely functional, although appropriate for official purposes, while preserving monastic simplicity:

The world famous “robes” of the Knights Templar, consisting of a tunic and cloak bearing the distinctive cross-paté, was not a ceremonial garment, but rather was the functional outer layer of contemporary military uniforms of the Middle Ages. This was dictated merely by practical necessity, because the chainmail armour in the desert heat of the Middle East could rapidly heat to extreme temperatures capable of actually burning into clothes or skin, unless covered by cloth to shield it from direct sunlight.

No White Robes – Despite numerous history books describing the classic Templar robes as “white”, and notwithstanding numerous fraternities aspiring to “Templar” affiliation wearing white robes, as a matter of historical fact they were not white. Rather, they were sand-coloured, as a light shade of beige, which in Old French was called ‘burell’, literally meaning “the color of butter”, as in the modern description of off-white “cream” color. This was appropriate as a desert “camouflage” color, and was practical to conceal occasional specks or smears of dirt during the course of active field work.

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD from Saint Bernard is evidence that the white robes from the first few years of the original Knights Templar were quickly ruled out. The original text (Rule 68) indicates that within less than 10 years after the Order was created, white was eliminated, and Templar regalia was ordered to be a natural “burell” shade of light brown [3]. That rule explained a major disadvantage of white robes as habits of the monks in Templar monasteries, as the specific reason why sand color must be used:

It was ordered that they “should not have white habits, from which custom great harm used to come to the house, for in the regions… false brothers… and others who said they were brothers of the Temple used to be sworn in, while they were of the world. They brought so much shame to us and harm to the Order of Knighthood that even their squires boasted of it, for this reason numerous scandals arose. Therefore let them assiduously be given black robes, but if these cannot be found, they should be given what is available in that province, or what is the least expensive, that is burell.”

This historical fact proves that the idea of white robes was specifically condemned by the early Knights Templar, precisely because they appealed to the “pride” (the “ego”) of the unworthy seeking self-aggrandizement. This establishes that white robes were considered to be contrary to the genuine core beliefs and principles of the original Templar Order. Therefore, real and authentic Templar Knights in fact wore light brown uniforms.

One explanation reveals why the famous early Templar robes were superficially perceived and commonly described as being “white”: In the extremely bright direct sunlight of the Middle East, the light brown “sand” color of Templar uniforms only appeared to be “white”, as an optical illusion. This subjective visual perception was enhanced by the sharp contrast between the sun-glared beige and any accessories or surroundings, making the robes seem more “white” by comparison.

Another explanation reveals how white robes with red crosses were popularized as supposedly “Templar” regalia, by confusion with the uniforms of medieval England: The Templar King Richard the Lionheart used white with straight-lined red crosses (different from the Templar cross-paté), although this officially represented Knights of the British Crown, and not the Templar Order. King Richard I of England ca. 1189 AD adopted tunics and banners with the flag of Saint George, a red cross on white [4] [5], which later became the flag of England under King Edward I ca. 1277 AD [6].

The historical fact of Templar robes being light brown is further confirmed by the regalia of the Eastern European Teutonic Knights, established in 1190 AD as a direct branch of the founding Western European Knights Templar [7]. The Teutonic robes are well-known to have been “brown”. This is because they were simply a darker shade of the Templar sand-brown, in order to better adapt to the dirt of woodlands and marshlands as field conditions instead of desert sand.

No Red Cross – The trademark tunic and cloak bearing the red cross was not established until 1146 AD, by order of Pope Eugenius, 28 years after the Order was created. While distinctive, and later of great fame due to worldwide renown of the Knights Templar, historians point out that this regalia proved to be a major strategic disadvantage, as “the red cross would also serve as a bulls-eye for the enemies’ arrows and lances.” That failed experiment of wearing large red crosses was abolished shortly thereafter. [8]

Because the controlling rule for Templar regalia was a requirement of practical utility in the field, the fact of this historical lesson learned establishes that wearing regalia with large crosses cannot be a part of any authentic regalia of the genuine Knights Templar tradition.

No Long Robes – The Temple Rule specifically rejected the idea of long flowing robes for decorative or ceremonial purposes. It allowed only “robes… without any show of pride” (Rule 18), condemned any “pride or arrogance” desiring a “better robe” (Rule 19), required “no excess of vice” in one’s dress (Rule 21), and explicitly prohibited “to have excess of… robes of length” (Rule 22). [9]

No Hooded Robes – An amendment to the Temple Rule (ca. 1150 AD) specifically commanded that “No [Templar] shall wear a hood on his head” (Rule 324), primarily because it suggests secrecy and a prideful mystique which are both strictly prohibited by Templar doctrines [10]. This proves that despite popularized artistic depictions, the short mantles of the original Knights Templar never had hoods. Monastic hoods were originally used for warmth in unheated churches of the European cold climate, but in the intense heat of the Middle East this could provoke heat exhaustion.

No Fantasy Robes – The Templar Patron Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, in his own words, directly confirmed the rules on “No Long Robes” and “No Hooded Robes”, in his speech In Praise of the New Knighthood (ca. 1136 AD), as he criticized the ceremonial style robes of other Orders of Chivalry:

“A warrior especially needs these three things: He must guard his person with strength, shrewdness and care; He must be free in his movements, and he must be quick to draw his sword. Then why do you blind yourselves… and trip yourselves up with long and full tunics… in big cumbersome sleeves?” (Chapter 2) [11]

Monastic Clothing – Historically, there was a general prohibition on Templars wearing gilded or decorated armour (on both people and horses). This was primarily for moral reasons, to avoid appealing to one’s “pride” (the “ego”), to avoid envy, and for the practical reason that in battle, “a greedy enemy would be more likely to attack a knight equipped with valuable armor rather than one protected by cheap steel.”

This originated the tradition of modesty and minimalism of Templar clothing. When not in battle armour, Templars were expected to wear simple monk’s robes, usually with solid brown colour being the main alternative to the sand-coloured dress robes [12].

No Decorative Shows – Saint Bernard also confirmed the rules on “No White Robes” and “Monastic Clothing” for practical real-world effectiveness, in his speech In Praise of the New Knighthood (ca. 1136 AD), as he sharply criticized – indeed ridiculed – the decorative equipment and glorifying accessories of other Orders of Chivalry:

He condemned “this monstrous error and… unbearable urge… [to] cover your horses with silk, and plume your armor… adorn… with gold and silver and precious stones, and then in all this glory you rush to your ruin… Do you think the swords of your foes will be turned back by your gold, spare your jewels or be unable to pierce your silks?” (Chapter 2)

“The [Templar] Knight of God differs from the knight of the world… When the battle is at hand, they arm themselves interiorly with Faith and exteriorly with steel, rather than decorate themselves with gold, since their business is to strike fear in the enemy rather than to incite his [covetous] greed. … They set their minds on fighting to win rather than on parading for show.” (Chapter 4) [13]

In the modern era, the Order of the Temple of Solomon has adopted the 14th century Rules of Chivalric Regalia as codified in 1672 AD [14], which were established as the international standard system in 1921 AD [15]. The historical precedent for surviving 12th century chivalric Orders adopting the international system is the Hospitaller Knights of Saint John (later Sovereign Military Order of Malta), which began to allow changes to its uniform in 1248 AD, and redesigned its regalia based on the British standards in 1831 AD [16].

In the modern era, the Order of the Temple of Solomon has adopted the 14th century Rules of Chivalric Regalia as codified in 1672 AD [14], which were established as the international standard system in 1921 AD [15]. The historical precedent for surviving 12th century chivalric Orders adopting the international system is the Hospitaller Knights of Saint John (later Sovereign Military Order of Malta), which began to allow changes to its uniform in 1248 AD, and redesigned its regalia based on the British standards in 1831 AD [16].

The restored Order of the Temple of Solomon is the direct continuation of the historical institution of the original Knights Templar from 1118 AD, as a sovereign subject of international law. As such, it should never copy the popularized eccentric costumes of private fraternities, which cannot be worn by official Templars and Crown Officers in real-world situations in professional environments.

Therefore, the Order has established regalia of an official character, true to its genuine and unique heritage, with doctrinal authenticity. The Templar uniform and insignia are conservative and relatively minimalist, while carrying the distinctive prestige of official capacity, and are fully in accordance with all customary rules and protocols for visible legitimacy.

Therefore, the Order has established regalia of an official character, true to its genuine and unique heritage, with doctrinal authenticity. The Templar uniform and insignia are conservative and relatively minimalist, while carrying the distinctive prestige of official capacity, and are fully in accordance with all customary rules and protocols for visible legitimacy.

The design of modern Templar regalia maintains a historical “period” look (used widely from the 14th-17th centuries), while benefitting from the continued use of that traditional style as the international standard system (from the 20th century into the present), which is still used by royal houses and many military services today. As a result, it is appropriate as sufficiently “old fashioned” to reflect almost 900 years of Templar heritage, without being too archaic or anachronistic.

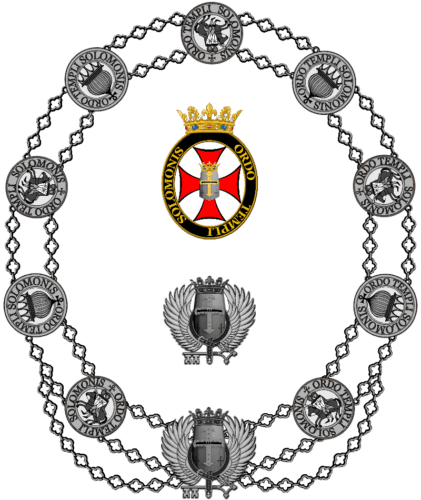

The Order has also reestablished proper use of the medieval Livery Badge and Livery Collar, as official insignia reserved for Chivalry and Nobility [17] [18], which were authorized to wear “at all feasts and in all companies” with all dress codes [19]. As a result, in situations where the uniform is not used, all Templars of the Order can rightfully use the relevant Livery badges and collars with smart casual dress, business dress or evening wear, expressing their official Templarism in diverse situations.

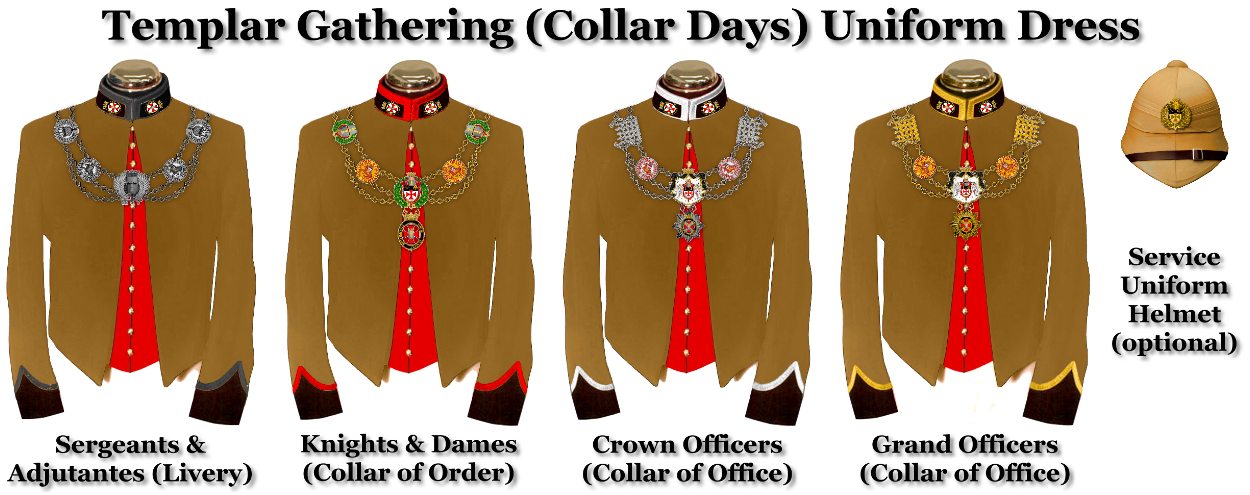

Following the customary rules, the Templar uniform is based upon the classic Mess Dress jacket, in the form of the Alternate Dress version of the customary Civil Uniform. The jacket is an open shell-coat design, short (above the waist) length without tails, known as “cutaway” or “cavalry” style Mess Dress, without buttons, and with a standing collar. It is accompanied by a high waistcoat.

Following the customary rules, the Templar uniform is based upon the classic Mess Dress jacket, in the form of the Alternate Dress version of the customary Civil Uniform. The jacket is an open shell-coat design, short (above the waist) length without tails, known as “cutaway” or “cavalry” style Mess Dress, without buttons, and with a standing collar. It is accompanied by a high waistcoat.

Historical authenticity of the genuine Templar tradition is preserved by the jacket being of sand-beige colour, having the same functionality and practicality of the historical regalia of the original Knights Templar. The waistcoat is red colour, reminiscent of the medieval red cross, which together with the black cuffs reflects the dominant heraldic colours of the Templar flag as a sovereign non-territorial Principality of statehood.

The modern Templar uniform provides a distinctive official look, with a casual feel. The open shell-coat design is perfect for a comfortable fit for both men and women. It is designed in full compliance with all customary rules to be versatile. The standing collar allows to avoid wearing a tie (with the collar clasp closed). The short above-waist length of the jacket keeps it out of the way, makes room for any utility holsters hanging below the belt (in field conditions), and gives maximal freedom of movement for active work.

The modern Templar uniform provides a distinctive official look, with a casual feel. The open shell-coat design is perfect for a comfortable fit for both men and women. It is designed in full compliance with all customary rules to be versatile. The standing collar allows to avoid wearing a tie (with the collar clasp closed). The short above-waist length of the jacket keeps it out of the way, makes room for any utility holsters hanging below the belt (in field conditions), and gives maximal freedom of movement for active work.

The black cuffs enable the jacket to pair with black trousers (or dress) to serve as proper “black tie” formal-wear. The sand colour of the jacket allows it to also be worn with khaki chino trousers (or dress) as functional day-wear. It is thus suitable for formal, semi-formal or informal dress. Instead of storing it in a closet only for rare events, modern Templars can fully enjoy their uniform for every-day use in diverse situations.

While looking modestly regal at ceremonial events, the Templar uniform blends in reasonably well in business or professional settings among lounge suits. It even complements safari wear for active hands-on field work, such as an archaeological expedition or survey site, or charitable volunteer work, whenever representing the Templar Order.

Made with a durable, extra lightweight fabric, it is comfortable to wear in cold climates with an open overcoat, or even in extremely hot climates of the equator, the southern hemisphere, Africa and the Middle East.

The original Templar Order was always essentially egalitarian. There were no “ranks” of knighthood or damehood, only levels of “office of duty”, in addition to the underlying chivalric status in equality.

The original Templar Order was always essentially egalitarian. There were no “ranks” of knighthood or damehood, only levels of “office of duty”, in addition to the underlying chivalric status in equality.

By historical precedent of the 12th century Teutonic Order, women as Templar Sisters wear the same uniform jacket as their Templar Brothers [20]. The Temple Rule of 1129 AD required “everyone to have the same” uniform (Rule 18), modified only by the Sergeants wearing black tunics, to distinguish them from the Knights (Rule 68) [21]. In the traditional British system, black is also associated with Sergeants [22], and red trim on the coat is associated with Knights of religious chivalric Orders [23]. In the international system, Crown Officers such as Diplomats are indicated by silver emblems, and high Crown Officers such as a Grand Mastery are indicated by gold emblems.

Templar Gathering Uniforms (Men)

Authentic to these historical precedents, all Templar uniforms are identical, modified only by the color of narrow embroidered braid edging (“trim”) on the collar and sleeves, and the relevant insignia. Accordingly, the levels of offices of service in the Templar Order are distinguished as follows:

Sergeants and Adjutantes have shiny black trim, with a Breast Badge of Order. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “dark steel” is authorized, to match the black trim, which can be worn as a substitute for the Collar of Office used at higher levels.

Temple Guardians have shiny black trim, with a Breast Badge of Order. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “light steel” is authorized, to complement the black trim, which can be worn as a substitute for the Collar of Office used at higher levels.

Squires and Ladies in Waiting (usually children of hereditary Knights or Dames) have red trim, with a Breast Badge of Order. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “rose copper” is authorized, to match the red trim, which can be worn as a substitute for the Collar of Office used at higher levels.

Knights and Dames have red trim, with a Neck (or Bow) Badge of Order. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “rose copper” is authorized, to match the red trim. A Collar of Order of “gold” metal is authorized for official events.

Crown Officers (including Diplomats) have silver trim, with a Neck (or Bow) Badge of Order, and a silver Breast Star. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “light steel” is authorized, to match the silver trim. A Collar of Office of “silver” metal is authorized for official events.

Grand Officers (including Ministers of Parliament) have gold trim, with a Neck (or Bow) badge, and a gold Breast Star. A Livery Collar (and badge) of “bronze” metal is authorized, to match the gold trim. A Collar of Office of “gold” metal is authorized for official events.

Donats of Devotion (patron sponsors) have a Neck (or Bow) Badge of Donat status (without uniform). A Livery Collar (and badge) of “bronze” metal is authorized, which can be worn as a substitute for the Collar of Office at special events.

Templar Gathering Uniforms (Collar Days)

The Knights Templar of the original Order were always based upon an Arthurian “round table” principle, without any artificial ranks or degrees, such that all Templars are equal. Accordingly, while some levels were held only as titles of office for active duty assignments, there were no rank insignia emblems worn on medieval Templar uniforms.

In the spirit of that tradition, the modern Order does not use any system of degrees or hierarchy of insignia for the chivalric aspect of the Order. Rank insignia on the shoulders are used only by career military or law enforcement officers serving in a governmental capacity with an official rank under the Ministry of Security of the Order as a sovereign subject of international law.

Templar Gathering Uniforms (Restricted)

All regalia and insignia of the Order of the Temple of Solomon are crafted to the highest standards as used by major royal houses and governments, made by world-class manufacturers who service such official historical institutions. The Order requires that each piece must have the look, feel, durability and time-tested high quality of the museum-grade historical artifacts which are their predecessors.

All regalia and insignia of the Order of the Temple of Solomon are crafted to the highest standards as used by major royal houses and governments, made by world-class manufacturers who service such official historical institutions. The Order requires that each piece must have the look, feel, durability and time-tested high quality of the museum-grade historical artifacts which are their predecessors.

Regalia of the Templar Order is thus designed to be heirloom legacy works. Whenever a member of the Order is elevated to a higher level of service, or retires from any office of duty, the previous or last held set of regalia is no longer worn, but is accumulated by the member to commemorate one’s record of service in the Templar Order. Such regalia from past or former service may be kept as family heirlooms and cultural artifacts, and used in private or public framed wall mount or mannequin displays in one’s home or office.

The official design concept for regalia of the Order enables all members to most fully experience and enjoy their place in Templar world heritage in the modern era, in their everyday lives. Instead of storing regalia in a closet only for some rare annual event, members can express an authentic Templar lifestyle at any and all times, in diverse real-world situations.

While carrying the distinguished prestige of representing the world-famous original Knights Templar, members of the Templar Order can also be confident in the conservative character of its regalia, consistent with the minimalist modesty of monastic simplicity, reflecting the classical Templar motto: “Non nobis Domine, sed nomine Tuo da gloriam!” (“Not to us Lord, but to Thy name give the glory!”)

Manufacturing Still in Progress – The images shown on this page are only illustrations, showing the official design concept as established by the Order. Manufacturing by a world-class governmental supplier has been arranged, but setup costs of the museum-quality Regalia required for a major historical Order has been a lower priority than budgets for humanitarian missions. All qualified members will be notified of Regalia supply as and when available.

Regalia Purchased Separately – Regalia must be purchased separately, after completing the Templar Skills Training program and Induction as a full Templar Brother or Sister. Regalia costs are not included in the subscriptions or donations made by members supporting the humanitarian missions.

Illustrations May Enlarge Sizes – For the purposes of Illustration, regalia accessories and insignia may appear larger than their actual size proportional to the clothing, for better visibility of detail. Actual sizes are strictly and precisely in accordance with the international standard rules as used by all governments and legitimate chivalric Orders.

See details of Regalia for General Membership in the Templar Order.

See details of Regalia for Knights and Dames in the Templar Order

See details of Regalia for Women in Membership in the Templar Order.

See details of Regalia for Donat Patron Sponsors of the Templar Order.

[1] Douglas Harper, Online Etymology Dictionary (2015), “Regalia”.

[2] John Yarker, The Arcane Schools, Manchester (1909), pp.341-342.

[3] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 68.

[4] The Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society (1891), Volumes 7-8, at p.139.

[5] W.G. Perrin, British Flags: Their Early History and Their Development, Cambridge University Press (1922), p.15.

[6] W.G. Perrin, British Flags: Their Early History and Their Development, Cambridge University Press (1922), p.37.

[7] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Teutonic Order”, p.541.

[8] Frank Sanello, The Knights Templars: God’s Warriors, the Devil’s Bankers, Taylor Trade Publishing, Oxford (2003), pp.14-15.

[9] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 18-19, 21-22.

[10] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 324.

[11] Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, Liber ad Milites Templi: De Laude Novae Militae, “Speech on Knights of the Temple: In Praise of the New Knighthood” (ca. 1136 AD); Translated in: Conrad Greenia, Bernard of Clairvaux: Treatises Three, Cistercian Fathers Series, No. 13, Cistercian Publications (1977), pp.127-145, “Chapter 2”.

[12] Frank Sanello, The Knights Templars: God’s Warriors, the Devil’s Bankers, Taylor Trade Publishing, Oxford (2003), pp.14-15.

[13] Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, Liber ad Milites Templi: De Laude Novae Militae, “Speech on Knights of the Temple: In Praise of the New Knighthood” (ca. 1136 AD); Translated in: Conrad Greenia, Bernard of Clairvaux: Treatises Three, Cistercian Fathers Series, No. 13, Cistercian Publications (1977), pp.127-145, “Chapter 2”, “Chapter 4”.

[14] Elias Ashmole, Institution Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, Hammet Publishing, London (1672), with engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar (33 plates), digitized by Folger Shakespeare Library.

[15] Herbert Arthur Previté Trendell, Dress and Insignia Worn at His Majesty’s Court, Harrison & Sons, for Lord Chamberlain’s Office, London (1921).

[16] Noel Cox, The Robes and Insignia of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, Arma: Journal of the Heraldry Society of Southern Africa (1999-2000), Issue 5.2.

[17] Peter Brown, A Companion to Chaucer, Wiley-Blackwell (2002), p.17.

[18] Chris Given-Wilson, Richard II and the Higher Nobility, in Anthony Goodman & James Gillespie, Richard II: The Art of Kingship, Oxford University Press (2003), p.126.

[19] Susan Crane, The Performance of Self, University of Pennsylvania Press (2002), p.19.

[20] François Velde, Women Knights in the Middle Ages, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003),”Women in the Military Orders”.

[21] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 18, 68.

[22] Herbert Arthur Previté Trendell, Dress and Insignia Worn at His Majesty’s Court, Harrison & Sons, for Lord Chamberlain’s Office, London (1921), Part I, “Full Dress and Levée Dress”, p.40.

[23] Herbert Arthur Previté Trendell, Dress and Insignia Worn at His Majesty’s Court, Harrison & Sons, for Lord Chamberlain’s Office, London (1921), Part I, “Full Dress and Levée Dress”, p.100.

You cannot copy content of this page