The modern Order of the Temple of Solomon honours the Treaty of Ramla of 1192 AD, reconfirmed by the Treaty of Acre of 1229 AD, establishing peace and cooperation between the Knights Templar and the Muslim Saracen Knights of Arabian Chivalry, to defend all Faith (of all religions), to uphold good over evil. The historical record, directly from 12th century sources, conclusively proves that the Templar Order was never against Islam as a religion, Muslims were in fact admitted to membership in the Templar Order as an exception, and the Sultan Salahadin himself was given the Templar Knighting Ceremony near Alexandria.

The modern Order of the Temple of Solomon honours the Treaty of Ramla of 1192 AD, reconfirmed by the Treaty of Acre of 1229 AD, establishing peace and cooperation between the Knights Templar and the Muslim Saracen Knights of Arabian Chivalry, to defend all Faith (of all religions), to uphold good over evil. The historical record, directly from 12th century sources, conclusively proves that the Templar Order was never against Islam as a religion, Muslims were in fact admitted to membership in the Templar Order as an exception, and the Sultan Salahadin himself was given the Templar Knighting Ceremony near Alexandria.

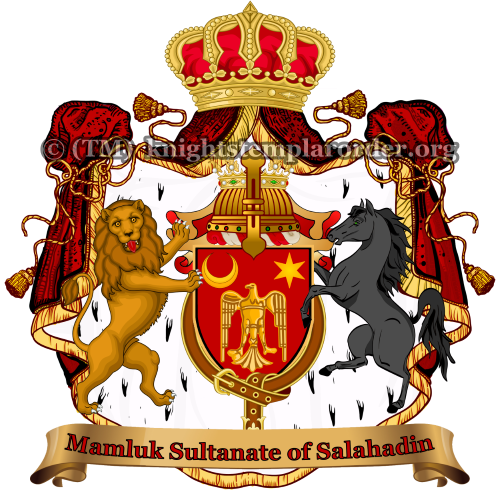

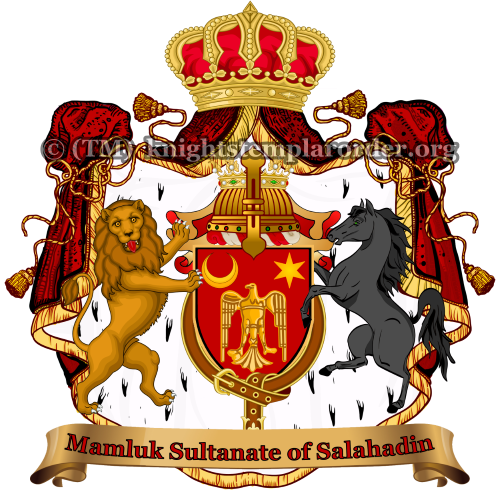

Official heraldic seal of the Knights of the Order of Saladin, under sovereign patronage of the Order of the Temple of Solomon

Muslims are not called “Templars”, but participate indirectly through parallel membership in the autonomous “Knights of the Order of Saladin”, under Sovereign Patronage of the Templar Order as a non-territorial Principality, united by the same Code of Chivalry of 1066 AD. By this authentic arrangement, Muslims enjoy full and equal participation in the general membership activities and events of the Templar Order, through the separate affiliate Order, while maintaining the distinct cultural identities of both Orders. This gives modern Templars the genuine medieval experience of interaction with their historical counterparts, in the finest tradition of mutual cooperation in true Chivalry.

Templars & Muslims are Separate – The Order of the Temple of Solomon supports the affiliated Knights of the Order of Saladin, which is separate and independent, with its own Charter by Templar sovereign Patronage. The Order of Saladin serves as the autonomous “Muslim branch” of Templar membership, such that Muslim members of Saladin enjoy full participation in the activities of the Templar Order.

Official heraldic coat of arms of the Knights of the Order of Salahadin, recognized by and participating in the Templar Order, under the Treaty of Ramla of 1192 AD

Quite contrary to popularized misconceptions, the Templars fully understood that Muslims were not necessarily enemies, that the real “enemies of Christ” could be even evil-doers pretending to be Christians, and that the “enemies of Christ” were generally the same as the enemies of Islam. Indeed, evil-doers are essentially the enemies of all Faith, opposed to the principle of religion itself, and are thus the enemies of God.

Therefore, the Templars were never “Crusaders” against Muslims, and did not agree with any such philosophy. Rather, the Knights Templar were Holy warrior-monks fighting for good against evil, regardless of which religions may or may not be involved.

The most conclusive evidence that Mulsims were in fact accepted in membership in the Templar Order was codified in the Temple Rule of 1129 AD, which was expanded by the later “Hierarchical Rules” added from ca. 1150-1250 AD:

One key amendment (ca. 1200 AD) specifically provides: “If a Brother goes out from the house and… enters into another religion, it would do no harm if he returns to rejoin the house; but he… will not be held by anything… to that religion nor to us also, for he has returned from the one and from the other.” (Rule 630) [2]

This was a major confirmation that a Templar could be a Muslim or even convert to Islam, and remain entirely in good standing within the Templar Order, declaring a principle of no-conflict and non-competition with Islam. The Muslim Knight is only required not to violate Templar rules, and is equally not obligated to do anything which would violate a doctrine of the other religion.

That fact that such a Rule was added is compelling evidence that the Grand Mastery had given permission to admit Muslims in many such cases over the years, giving rise to the necessity of codifying the amendment. The mere existence of this Rule proves that the Templars authentically regarded all religions as fundamentally compatible, and rejected the idea that doctrines of different religions could ever really be in conflict.

In 1167 AD, during a truce Saladin “met in the camp of King Amalric of Jerusalem, outside of Alexandria [with] the Christian Knight, Humphrey of Toron.” Saladin requested for “his new-found friend to acquaint him with the principles upon which this renowned organization was founded, and the manner in which knighthood was acquired.” Many historians concluded that “With such enthusiasm for its fundamentals, and with the glow of sympathy inspired by their new-found friendship, [it was] natural… that the pupil [Saladin] should ask and the instructor grant initiation into the Order”. [3]

A similar event dated ca. 1190 AD reported that Saladin was officially given and fully received knighthood by formal induction into the Order of the Temple of Solomon. Supported by references in 12th century chronicles, a more detailed account was written in 13th century manuscripts dated ca. 1250 AD, fully describing the event, which was the author’s direct personal experience within his own lifetime. Those manuscripts, written by “Count Hue de Tabarie” and entitled Ordene de Chevalerie (“Order of Chivalry”), documented the following historical account:

During the third crusade (ca. 1189-1192 AD), the Templar Knight Count Hue de Tabarie (also written as “Hues de Taberie”, meaning “of Tiberias” of the Kingdom of Jerusalem) was captured by the Sultan Saladin. Saladin announced that he “admired the gentlemen of the Knights Templar”, and expressed his desire to become one of them as a Brother in Chivalry. Saladin requested that Count Hue perform the Templar knighthood induction ceremony on him, promising in exchange the unconditional release of the captured Knight. The sacred ceremony was performed, and Saladin, satisfied that he was now officially a Brother Knight of the Templar Order, released Count Hue as promised. [4]

It is generally believed by historians that Saladin wished both to better understand his nemesis Templar colleagues in Chivalry, as well as to share an honorable bond with them in furtherance of emphasizing their commonalities and making peace. It is also believed that the investiture ceremony he received, while official, traditional and authentic, may have been slightly modified so as not to violate Saladin’s Muslim Faith.

The authoritative 18th century historian François-Louis-Claude Marin possessed “two curious Manuscripts on the Chivalry of Saladin”, which the French Royal Academy of Inscriptions had granted him permission to publish. Both were copies of L’Ordene de Chevalerie by “Hues de Tabarie” from ca. 1250 AD, classified as “antique manuscripts, one in prose”. This evidences that the second manuscript version, L’Ordre de Chevalerie, was not a “poem”, and not “literary” (as the former is sometimes considered), and thus that the Knighting of Saladin by Hue de Tabarie was also a factual chronicle from the historical record. [5]

Both manuscripts were first published in the academic treatise Histoire de Saladin by François Marin in 1758 AD, which was granted Royal “Approbation and Privilege” by King Louis XV, confirming their validity as official sources of the historical record suitable for scholarship. That two-volume history treatise was published one year before the famous literary version L’Ordene de Chevalerie reprinted by Etienne Barbazan in 1759 AD [6], thus confirming that the two manuscripts from the François Marin edition were the primary historical sources for the Templar Knighting of Saladin.

The 12th century Crusader, Oxford scholar and historian Geoffrey de Vinsauf also recorded a contemporary account of the Templar Knighting of Saladin: “In the process of time, when his years were matured… he came to Enfrid of Tours, the illustrious Prince of Palestine, to be mantled, and after the manner of the Franks [Templars] received from him the belt of knighthood.” [7] [8]

Although the account of Geoffrey de Vincauf appears to be an alternate event, additional historical facts in context establish that it is the same event as in the Hue de Tabarie manuscripts:

Enfrid of Tours married Princess Elizabeth, the daughter of Queen Maria of Jerusalem with King Amalric I, which places this event during the period ca. 1170-1190 AD. [9] Queen Maria’s other daughter Margaret married “Hugh of Tiberias”, a Templar Knight and colleague of Enfrid, directly connecting the reference to Enfrid with the more specific records of the Knighting of Saladin by “Hue de Tabarie”, which is dated to ca. 1190 AD.

This makes sense, because Enfrid was Prince of Jerusalem, and not otherwise known to be a Knight of the Templar Order itself. Accordingly, such knighthood as requested of Enfrid could only be performed by an official Templar Knight such as Enfrid’s colleague Hue de Tabarie, at which Enfrid could attend representing the Royal Patronage of the Order. These supporting facts confirm that the 13th century manuscripts of L’Ordene de Chevalerie report the same event which is confirmed by contemporary 12th century sources.

Although the Muslim chroniclers make no mention of any event of the Templar Knighting of Saladin, European historians generally conclude that “Possibly, after reflection [Saladin] thought it just as well not to mention it… [realizing] that the older generation has its prejudices which preclude both reason and argument, and that on occasion it is better to let sleeping dogs lie undisturbed.” Most likely for this same reason, the Knights Templar also kept manuscript records of such event relatively private, such that the historical account did not emerge for the general public until 1758 AD, over 450 years after the French persecution of the Order.

Western historians note that the Templar Knighting of Saladin was recorded “Not only in poetry and romance, but in serious records of events. Sometimes the ceremony has been affirmed, but the manner of it varied.” Further indirect evidence supports that this event occurred: Saladin also “gave his approval to the knighting of his brother’s son, a performance conducted with much ceremony before the whole Christian army by no less a person than Richard the Lion-Hearted.”[10]

One thing is certain, as a matter of historical fact: The original Knights Templar themselves believed and formally documented that the Sultan Saladin had received induction of knighthood in the Order of the Temple of Solomon by 1190 AD, and thereafter considered Saladin to be wholly accepted in the Order as a “Templar Brother”, revered for upholding its principles in a most exemplary manner.

Verified Templar history, from authentic sources of the original Order itself, admit and confirm that the Grand Mastery officially considered the leader of Muslim Saracen Chivalry, the Sultan Saladin himself, to be a Templar Brother Knight in the Order of the Temple of Solomon as of ca. 1190 AD. Therefore, the legitimate continuation of the Templar Order cannot possibly deny the proven history that Muslims were (and must continue to be) authentically accepted as full and equal members of the Order.

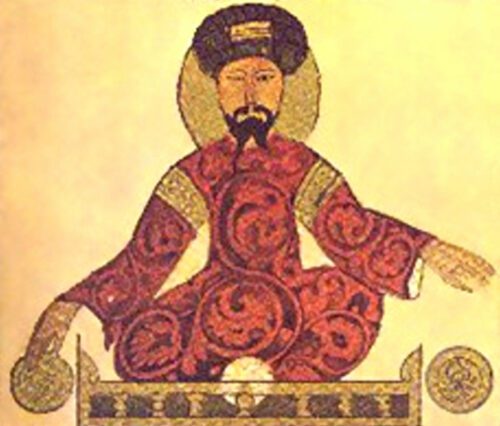

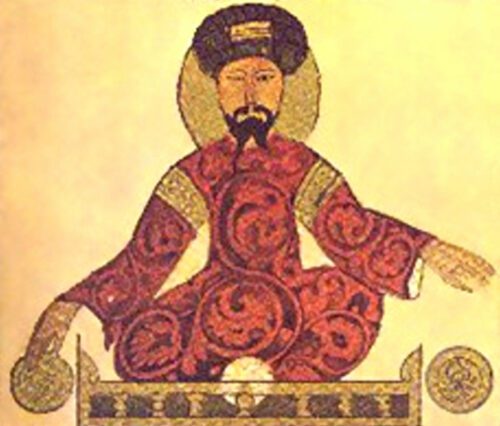

‘L’Armée de Saladin’ (1337 AD) in ‘Histoire d’Outremer’ by Guillaume de Tyr (William of Tyre), illumination on parchment, in Biblioteque Nationale de France, Paris (MSS Fr. 22495 Fol. 229v)

This new brand of Chivalry (Furúsiyyah) (فروسه) spread from the Arabian Peninsula through the 8th century Muslim “Moors” of the Iberian Peninsula (covering Spain, Portugal, Andorra and part of Southern France). It was the Provençal Troubadours from the Arab courts in Andalusia (Spain) who adopted these ideals, and famously helped to spread the medieval culture of Chivalry across Europe. [12]

Arabian Chivalry was entirely focused on the principles of “Virtue” and “Honour” (Old Arabic: Múruwwa) (مروه), which were considered even more important than religious doctrines [13], and was the source of ancient ideals of Quests of the Knight Errant and the romantic aspects of Chivalry [14].

Therefore, authentic Templarism cannot possibly reject nor oppose the very same Muslim Chivalry which made substantial contributions to its finest traditions and most inspired humanitarian ideals, and which remains a central part of genuine Templar heritage.

‘Salah Ad-Din Jusuf Ibn Ajub’ (Saladin), illumination in 12th century Arabian Codex, in the British Library

According to the Sufi Master and historian Sayed Idries el-Hashimi (1924-1996 AD), known as “Idries Shah”, the Al-Banna Sufis from Egypt helped the founding Templars to understand and master their archaeological findings from the Temple of Solomon, teaching and training the first Knights Templar during their formative nine years of excavations. The Al-Banna Order provided key knowledge of the ancient origins of Christianity, saying “You may have the Cross, but we have the meaning of the Cross.” [15]

The mystery school masters of the Muslim (Sunni) Sufi Hashashin Order (“Assassins”) provided additional training over the years, for restoration of the Ancient Priesthood which the Templars recovered from the Temple of Solomon. Their Arabian Magi “ascended master” Grand Master Rashid Al-Din Sinan (1132-1192 AD) came to be affectionately known by the Knights Templar as the “Old Man of the Mountains”. [16] The Muslim (Shi’ite) Sufi Isma’ili Order also made many significant contributions to the infrastructure and institutional organization of the Knights Templar as a Chivalric Order. [17]

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD commands that the traditions of Templar Chivalry must be “guarded purely and durably” (Rule 2), and that the full heritage of the Templar Order “must not be forgotten, and… must be guarded firmly.” (Rule 8) [18]

Therefore, the traditions of Arabian Chivalry and mysticism are also genuine parts of the Templar heritage, which all Knights and Dames of the Order are sworn to preserve and continue for the benefit of humanity. Accordingly, the Order has a clear moral obligation, as one of its authentic historical missions, to restore and share those treasures of Muslim heritage, as a gift back to the Muslim and Sufi communities in the modern era, in gratitude for their own major contributions to the positive development of civilization.

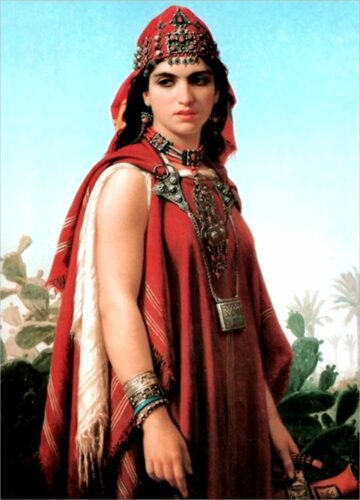

‘Berber Woman’ (from Egypt region of Arabia), painting by Emile Vernet-Lecomte (French artist 1821-1900 AD)

By long-standing Saracen tradition, “During war, women often accompanied their men to battle, but they were usually stationed behind the lines.” [19] This historical practice establishes the precedent that Arab or Muslim women can also participate in the social events and activities of Chivalry together with their husbands as a couple, or in support of their chivalric brothers.

Arab historians documented that in 1248 AD the Sultan As-Salih Ayyub (a successor of Saladin) had deteriorating health, while under pressure of a planned “Seventh Crusade” to invade Egypt led by the French King Louis IX. The Sultan’s wife Shajar Al-Durr called a meeting of all the Generals, became Commander in Chief of the Egyptian forces, and successfully defended Egypt against the French attack, inflicting heavy losses on the invaders. [20] This active leadership and military victory of Princess Shajar is a prominent historical precedent, proving conclusively that Muslim women can also actively participate in all activities and missions of Chivalry.

From ancient Arabian culture, women “were regarded not as slaves and chattels, but as equals and companions. … The [romantic] Chivalry of the Middle Ages is, perhaps, ultimately traceable to [ancient] Arabia. … But the nobility of the women is not only reflected in the heroism and devotion of the men; it stands recorded in song, in legend, and in history.” A women named Fátima “was one of three noble matrons who bore the title… ‘the Mothers of Heroes’.” [21] This evidences that women in general membership in a tradition of Chivalry can hold a similar title of honour, indicating that they are the “Sisters of Heroes”.

That key treaty was restored and reconfirmed by the Treaty of Acre of 1229 AD between Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and Saladin’s successor Al-Kamil, supporting mutual cooperation of the Knights Templar with Muslim Saracens in preserving Holy sites and heritage. [24]

Official heraldic coat of arms of the Knights of the Order of Salahadin, recognized by and participating in the Templar Order, under the Treaty of Ramla of 1192 AD

Such joint Templar-Muslim cooperation continues today, expanded to general restoration of the collective sacred knowledge and underlying principles of Faith which belong to all of humanity, together upholding those pillars of civilization.

While the modern Order of the Temple of Solomon preserves its own Christian traditions, as well as its more ancient origins as the foundation of all spiritual religions, its membership is otherwise interfaith and non-denominational.

The Order understands that Islam requires a special approach to accommodate Muslim members: Instead of calling Muslims “Templars”, giving the appearance of them adopting Christian traditions, the Order prefers to fully respect and preserve authentic spiritual Islam in its own right, and to support and celebrate the integrity of its Arabian traditions which Muslim members contribute to the Order.

Supported by active guidance and consultation from authorities of Islam (at Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo), the Templar Order has recovered and restored many essential traditions of the Sultan Saladin, Arabian Chivalry and related elements of Sufi heritage.

Ironically, as the legitimate historical institution of the original Knights Templar from 1118 AD, vested with its own inherent and independent Fons Honourum Crown authority since 2013 AD, the Order uniquely possesses the relevant “heraldic jurisdiction” to “recognize” the authenticity and legitimacy of its own historical “enemy” from the 12th century (also as the direct legal counter-party to its own peace treaty since 1192 AD) [25] [26].

Accordingly, the Order exercised its legal capacity as a sovereign Principality under customary international law, to grant a Charter of “recognition” and Sovereign Patronage to the authentic “Knights of the Order of Saladin”.

The Order of Saladin was reestablished as an autonomous organization parallel to the Order of the Temple of Solomon, such that the Templars provide a center of operations and supporting infrastructure to the Saracen partner Order. In this way, the Templar Order presents a gift of reconciliation and appreciation to the Muslim world, embodied in the restored chivalric Order of Saladin backed by Templar Patronage.

Just as the Muslims gave a gift of ancient heritage of the origins of Christianity to the founding Knights Templar, the modern Templar Order now reciprocates by giving back key elements of the heritage of ancient Arabian Chivalry and sacred knowledge to the Muslim world.

All Muslims who exemplify and are dedicated to the Code of Chivalry of 1066 AD, following the example of Saladin, who see themselves as connected with the Knights Templar by shared spiritual values and common core beliefs, are admitted to the Knights of the Order of Saladin. Membership is granted by “sovereign recognition” from the Templar Order, recognizing that each person genuinely represents and thereby belongs to the authentic tradition of Saladin.

All members of the Order of Saladin are thereby automatically considered to be in full membership and active participation within the Order of the Temple of Solomon. In this way, the Order of Saladin effectively serves as the “Muslim side” of the Templar Order.

This arrangement allows Muslim members to preserve their distinct cultural identity in accordance with the customs of Islam, while giving full and equal access to membership benefits and all forms of participation in the Order. Muslim members thus actively engage with Templars within the Order of the Temple of Solomon, not by compromising to adopt Christian culture, but rather by faithfully representing their own religion, and by preserving and embodying the Arabian Chivalry of Saladin.

(The name of the Order of the Hashashin, often called the “Assassins”, actually derives from the medieval Arabic word Háshia meaning a “Royal Order” of knighthood. It was the Hashashin who taught the Templars about the ancient Djedhi Priesthood of Egypt as part of Sufi heritage.)

Official heraldic seal of the Knights of the Order of Salahadin, recognized by and participating in the Templar Order, under the Treaty of Ramla of 1192 AD

In classical and modern Arabic, a synonym for Háshia which more generally means an “Order of Knighthood” is ‘Wazzára’ (وزاره). Directly connected with this, the medieval Old Arabic word for “Knight of a Royal Order” is ‘Wazzír’ (وزير), and a “Dame of a Royal Order” is ‘Wazzíra’ (وزيره).

(The Pharaonic Egyptian word for a priest who held the staff of power was formed by the hieroglyphs “WSR”, pronounced “Wassir”. The name of Osiris was pronounced “Ausir”, and he was also called “Wassir”. The spine of Osiris was the Djed pillar of spiritual strength, the primary symbol of the ancient Djedhi Priesthood, who were considered a “knightly” type of priests and priestesses. The later Celtic and Old English word “Wizard” derived from the ancient Egyptian Wassir, which became the Arabic Wazzir for a “Knight of a Royal Order”.)

Therefore, the parallel institution for Muslims in membership with the Order of the Temple of Solomon properly holds the chivalric name of the “Knights of the Order of Saladin” (Wuzzará min Háshia Salahadín) (وزراء من حاشية صلاح الدين). Just as Knights of the Order of the Temple of Solomon are informally and unofficially called the “Knights Templar”, the Knights and Dames of the Order of Saladin can be referred to by the informal short form “Knight (Dame) of Saladin” (Wazzír(a) min Salahadín) (وزير من صلاح الدين).

In Arabian Chivalry of the tradition of Saladin, the correct equivalent prenominal styles of address are: “Saídi” (“Sir” for a Knight) (سيدي), and “Saídatí” (“Dame”) (سيدتي).

The Arabian chivalric title Saídi was used as “Sir” for a Knight on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. There it was often pronounced ‘As-Sayyid’, used as “Lord” for nobility, which thus became the near-sounding Spanish title “El Cid”. [27]

The title Saídi for a Knight is also the name of a specific dialect of Arabic language, which is unique to the region of “upper Egypt”, associated with its capital Thebes in modern Luxor. The dialect itself is characterized by the frequent use of medieval Old Arabic words and phrases of honour and respect in social discourse. Calling it “Saídi”, literally the “Knightly dialect of nobiliary Sirs”, reflects the uniqueness of the Luxor region as the heartland of ancient Arabian Chivalry (Al-Furúsiyyah Al-Arabiya) (الفروسا العربيه). In the modern Templar Order, Luxor is a major site of Holy pilgrimage to sites of the Templar Priesthood, and also of the medieval world of the tradition of Chivalry of the Sultan Saladin.

For the primary entry-level category of membership in the Order of Saladin, the Arabic title for a man is ‘Musá’ed Wazzir’ (مساعد وزير) (Sergeant), and for a woman is ‘Musa’éd’it Wazzir’ (مساعدة وزير) (Adjutante), both literally meaning “Assistant to Royal Knights”.

Membership Certificates for the Knights of the Order of Saladin are issued with the proper Saracen heraldry of Saladin, and with bilingual indications of both the Arabic and corresponding English titles. Muslim members can freely choose to use either (or both of) the Arabic or English versions of their titles, as they may deem appropriate or practical for their personal style and local cultural and professional environments.

Alternative regalia insignia authentic to the tradition of Saladin will be provided for Muslim members. In this way, both the Knights Templar and the Knights of Saladin wear the same matching uniforms, visibly declaring Christian-Muslim unity in equal partnership, while also demonstrating and celebrating the respective historical traditions which each represent.

Click for a full presentation of Muslim Saracen Chivalry as Templar heritage.

Click for information on General Membership in the Templar Order.

Learn about authentic Modern Templar Missions as membership activities.

Learn about the Real Enemies of the Order which Templars oppose.

[1] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 2, 14, 57.

[2] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, “Hierarchial Rules”, Rule 630.

[3] Charles J. Rosebault, Saladin: Prince of Chivalry, Robert M McBride & Co, New York (1930), Chapter 1, “The Knighting of Saladin”, pp.1-3; Citing: Richard of Devizes & Geoffrey de Vinsauf, Chronicles of the Crusades: Contemporary Narratives of the Crusade of Richard Coer de Lion (12th century), Henry G. Bohn, Covent Garden, London (1848).

[4] Hue de Tabarie, L’Ordene de Chevalerie (French manuscript, dated ca. 1250); Reprinted in: Etienne Barbazan, L’Ordene de Chevalerie, Chaubert & Claude Herissant, Paris (1759); Cited in: Brad Miner, The Compleat Gentleman: The Modern Man’s Guide to Chivalry, Spence Publishing Company, Dallas, Texas (2004), pp.43-44.

[5] François-Louis-Claude Marin, Histoire de Saladin: Sulthan D’Egypte et de Syrie, published with Royal Approbation and Privilege of the French King Louis XV, Libraire Tilliard, Paris (1758), Volume 2, pp.445-446. (Text of the 13th century manuscripts L’Ordene de Chevalerie and L’Ordre de Chevalerie published in Volume 2, pp.447-483.)

[6] Etienne Barbazan, L’Ordene de Chevalerie, Chaubert & Claude Herissant, Paris (1759).

[7] Charles J. Rosebault, Saladin: Prince of Chivalry, Robert M McBride & Co, New York (1930), Chapter 1, “The Knighting of Saladin”, p.5.

[8] Geoffrey de Vinsauf, History of the Expedition of Richard Coeur de Lion to the Holy Land (12th century), Translation from Latin, published in: Richard of Devizes & Geoffrey de Vinsauf, Chronicles of the Crusades: Contemporary Narratives of the Crusade of Richard Coer de Lion, Henry G. Bohn, Covent Garden, London (1848), Part 2, pp.65-339, Chapter 3, p.72.

[9] Richard of Devizes & Geoffrey de Vinsauf, Chronicles of the Crusades: Contemporary Narratives of the Crusade of Richard Coer de Lion, Henry G. Bohn, Covent Garden, London (1848), Part 2, pp.125-126.

[10] Charles J. Rosebault, Saladin: Prince of Chivalry, Robert M McBride & Co, New York (1930), Chapter 1, “The Knighting of Saladin”, pp.4-5.

[11] Habeeb Salloum, Saladin Chivalry and the Crusades, Al-Hewar Center for Arab Culture and Dialogue, Washington DC (2005).

[12] Titus Burckhardt, Moorish Culture in Spain, McGraw-Hill (1972), Reprinted by Fons Vitae (1999); Habeeb Salloum, Saladin Chivalry and the Crusades, Al-Hewar Center for Arab Culture and Dialogue, Washington DC (2005).

[13] Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, A Literary History of the Arabs, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York (1907), Reprinted by Cosimo Classics (2010), p.178, 287.

[14] Lady Anne Blunt & Wilfrid S. Blunt, The Seven Golden Odes of Pagan Arabia, London (1903), Introduction, p.14; Quoted by: Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, A Literary History of the Arabs, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York (1907), Reprinted by Cosimo Classics (2010), p.88.

[15] Idries Shaw, The Sufis, The Octagon Press, London (1964), 2nd Edition (1983).

[16] Edith Miller, Occult Theocracy, Hawthorne, California, The Christian Book Club of America (1993), p.143.

[17] Edward Burman, The Assassins – Holy Killers of Islam, Crucible Press (1987).

[18] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 2, 8.

[19] Habeeb Salloum, Muru’ah and the Code of Chivalry, Al-Hewar Center for Arab Culture and Dialogue, Washington DC (2005).

[20] Abdul Ali, Islamic Dynasties of the Arab East: State and Civilization During the Later Medieval Times, M.D. Publications (1996), p.36.

[21] Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, A Literary History of the Arabs, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York (1907), Reprinted by Cosimo Classics (2010), p.88.

[22] Facts on File Library of World History, Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, Africa (2009), “Saladin”, p.386.

[23] J. Gordon Melton, Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History, ABC-CLIO Publishing (2014), “1192”, “September 2, 1192”, p.786.

[24] Joseph W. Meri & Jeri L. Bacharach, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Taylor and Francis (2006), p.84.

[25] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 5.

[26] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.416.

[27] Pir Zia Inayat-Khan, Saracen Chivalry: Counsels on Valor, Generosity and the Mystical Quest, Suluk Press, Omega Publications, New Lebanon New York (2012), Glossary: “El Cid”, p.175.

You cannot copy content of this page